The San Francisco Oil Spill of 1971

When the People Took Action and Saved Bolinas Lagoon

(and changed the country)

The first Earth Day was held on April 22, 1970, at a time when politicians, corporations, and the mass media believed that the environment was not a concern of most of the populace. To their great surprise, 20 million Americans participated in over 14,000 events around the country.

Environmental historian Adam Rome observed that:

“Earth Day 1970 was a powerful organizing tool. It wasn’t just a demonstration − it empowered people to continue working for change.”

Front page on the day after first Earth Day of April 22, 1970

Fifty years later, the planet is in crisis, but the environmental movement “has lost its revolutionary fervor, instead prioritizing token gestures and a focus on individual action in place of political upheaval.” Earth Day now “is not nearly as much about collective action to deal with huge problems as it was in 1970.”

This is the story of people working cooperatively, supported and strengthened by a mass movement, who dealt with an environmental crisis and continued working for change.

For citations to all facts and quotations herein, see Notes and Sources: The San Francisco Oil Spill of 1971: https://www.necessarystorms.com/home/notes-and-sources-the-san-francisco-oil-spill-of-1971.

Title photo: Pierre La Plant, SmugMug

PROLOGUE: JANUARY, 1971

San Francisco Bay in winter is a hub of clamorous activity, filled with migrating sea birds announcing their arrival, small boats chugging out to catch Dungeness crab, seals barking and splashing, and storm-driven waves crashing against rocks and shores. When the herring begin their annual run, thousands of screaming, squawking birds engage in a feeding frenzy.

Common murre colony on the Farallons (Photo: Duncan Wright, Sabine’s Sunbird)

Nights on the bay are quieter. Grebes, scoters, and common murres settle down to sleep on the water. Nights are more treacherous thirty miles west of the Golden Gate, on the jutting rock islands known as the Farallons. Gulls and cormorants roost on cliffs there, where they cope with many dangers: owls drawn by the large population of mice; great white sharks on the hunt; leaks from hundreds of shipwrecks over the past two centuries; and the remnants of the 47,500 containers of radioactive waste dumped between 1946 and 1971 when the Farallons “served as the nation’s primary nuclear waste dumping ground.”

But on a fateful night in January 1971, the birds on the Farallons were the lucky ones.

THE COLLISION

On January 18, 1971 − less than a month after creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, less than a year after the first Earth Day, and almost exactly two years after the horrific Santa Barbara oil well blowout − fog horns blasted warnings as pea-soup fog blanketed San Francisco Bay. Local airports closed operations. But even in the middle of a night with zero-visibility conditions, Standard Oil of California moved ships in and out of its Richmond refinery.

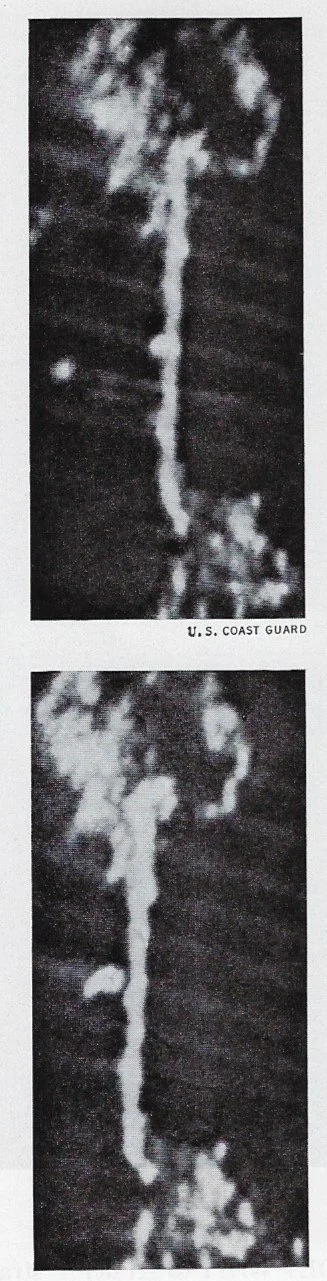

Radar images. Vertical line is the Golden Gate Bridge. Top image shows the Arizona to left, the Oregon just under bridge; in bottom photo, the two dots have merged.

At 1:40 AM, two tankers approached the Golden Gate Bridge. The Arizona Standard was on its way to the refinery with nearly five million gallons of crude. The Oregon Standard was outbound, heading for British Columbia with over four million gallons of bunker oil. Neither tanker had a pilot on board. And as was the case with almost every tanker in the world, neither was double-hulled.

On Pier 45 in San Francisco, Coast Guard technicians were testing a “novel radar system.” They watched their screens in helpless horror as the two blips drew too close to each other, threatening to merge into one. “Frantic calls to the captains failed to get through.”

The Arizona rammed its bow forty feet into the Oregon, piercing its hull and tearing open six of the 26 oil storage compartments. Bunker oil began pouring into the bay.

Seals on a buoy in Richardson Bay, near Tiburon.

Bunker oil is made from the dregs of crude oil refining. It’s the fuel used by cargo ships. It is carbon-intensive, loaded with sulfur, and highly polluting. It’s also viscous, “pitch black and thick as molasses.” It is “one step removed from crude oil.”

Almost immediately the birds sleeping on the water were covered with oil. Seals tried to escape by climbing onto rocks or piers but the rocks and pier pilings were coated with the slippery goo.

The two disabled behemoths, stuck together, drifted into the bay, eventually running up against Angel Island. The Oregon continued leaking.

“Much of the oil…began to drift seaward” as the tide went out at 5:30AM. The oil slick outside the bay split in half, some going north and the rest south. “Beached oil” came into the bay, where it fouled the Sausalito and Tiburon waterfronts, the Berkeley marina, Angel Island, and Fisherman’s Wharf.

By 6:00AM on January 19, 28 hours after the collision, oil coated the beaches north of the Golden Gate and the western shores of San Francisco.

Twelve hours after the collision, oil fills the golden gate and has spread inside the bay. The Marin Headlands to the left and Sausalito, just above the bridge, are already fouled. Angel Island is at the top of the screen, across from Tiburon. (National Geographic, Western Aerial Photo Company)

The slick headed toward Bolinas and Point Reyes.

BOLINAS AND POINT REYES

The large peninsula of Point Reyes is separated from the mainland by the rift of the San Andreas Fault. Concerted efforts by citizens over decades had saved it from various development proposals and in 1962 the Point Reyes National Seashore was authorized.

At the very bottom of the peninsula sits Bolinas, a small town that in 1970 had less than 1,000 residents. Isolated by choice, Bolinas had been a bohemian enclave since the 1950s, home to beat poets and artists. The Sixties counterculture found a haven in Bolinas, too.

On the inland side of Bolinas, behind high cliffs on one side and a sand spit on the other, is a narrow passageway, 163 feet across. This is the mouth to Bolinas Lagoon, “one of the last untouched lagoons on the California coast.” The varied terrains of the 1500-acre estuary — open water, mudflats, and marshes — make the Lagoon a major stopover for migrating waterbirds, as well as a year-round home for hundreds of species of birds, fish, insects, and reptiles. Many of the species found there are endangered and some are found nowhere else in the world. It’s also a site for seal haul-out.

Bolinas Lagoon at low tide. Stinson Beach is at left. The town of Bolinas is above the lagoon mouth. Duxbury Point juts from the NW corner of Bolinas, and Agate Beach is on the ocean side of the town. (Photo: U.S.Army)

SAVING BOLINAS LAGOON

On January 19 Tom D’Onofrio, a Bolinas resident and sculptor, woke at 6:00AM to the voice of Dave McQueen on the radio. The well-known KSAN announcer warned that the oil slick was heading to Bolinas.

D’Onofrio jumped on his horse and rode to the cliff above Agate Beach, where he had surfed the previous afternoon. He could smell the oil before he got there. Behind him the sun was just peeking over Mount Tamalpais, bathing the ocean in light.

“I got there and looked down and the beach was covered with oil. It was on the rocks, the waves, the logs. Everything. And I started to cry.”

D’Onofrio knew that the tide would come in at half past noon, so time was of the essence. He’d worked in a logging camp and thought that a boom (a row of logs strung together) could be constructed across the narrow mouth of Bolinas Lagoon to create a barrier, bolstered with hay to soak up the oil. He rode to his neighbor, John Armstrong, a boat builder who had a large supply of logs. Armstrong agreed to help. D’Onofrio then sped to the local café, Scowley’s, and leaped onto the counter, probably astonishing even the freaks of Bolinas.

Cliff at Agate Beach two days after the oil spill. (Jonathan S. Blair, National Geographic)

“There’s oil off shore and it’s coming this way,” he announced. “We need every able-bodied man, woman, and big child.” The café emptied as everyone rushed to the mouth of the lagoon. Other residents converged too − hundreds of them.

Officials of local and state government also arrived along with Standard Oil representatives. As Armstrong backed his truck full of logs onto the sand, the officials shouted at him and the residents to stop or face arrest. “The young people − honed by 1960s counter-culture activism” − ignored them.

Toby’s Feed Barn in nearby Point Reyes Station drove down with loads of hay. Horse owners brought more. “A small flotilla of boats” helped position the logs. There wasn’t enough time to build a sturdy boom over the mouth of the Lagoon, so the people built three makeshift dams.

Luck was with them; the ocean was unusually calm for that time of year. D’Onofrio remarked later that “if it had been stormy, nothing we did would have worked.” The tide came in at three feet high instead of five, and a brisk north-blowing wind kept some of the oil away from the lagoon’s entry channel. At 6PM Audubon Society naturalist Clerin Zumwaldt said that “We were really lucky…The barriers didn’t hold as well as we thought, but with the tide and the wind, not much oil got inside the lagoon.”

Oiled grebe. (From International Bird Rescue web site)

The beaches on the Pacific side were already covered with oil. Birds drenched in oil were washing up by the hundreds, up and down the coastline and in the bays and estuaries. (Bird rescue efforts are described below.) So far the birds in the lagoon were not injured. But to keep them safe, oil had to be blocked from getting in.

At midnight the tide broke up the hastily constructed barriers. People worked through the night spreading hay at the mouth of the lagoon and on the beach, removing the oil-soaked hay and replacing it with fresh in a constant human chain.

Meanwhile “Captain Spatula” of Scowley’s, the Bolinas café, delivered 40-gallon barrels of coffee and wheelbarrows of hamburgers to feed the volunteers. People were arriving from all over the Bay Area bringing food, shovels, and blankets and towels for the birds. A band played to boost the morale of the workers.

Those who were physically compromised worked phone lines. Pacific Telephone installed emergency phones throughout the spill area and helped set up ham radio units in Bolinas and Tiburon. Traffic had to be coordinated, because then (and now) Bolinas and Stinson Beach were only accessible by small roads that branched off the narrow, twisty, two-lane Highway One. The Marin Ecology Center established a ride network.

Standard Oil arranged for hay to add to that supplied by Toby’s Feed Barn. One phone bank volunteer said that the volunteers would decide what was needed, make calls to get it, and tell them to send the bill to Standard Oil.

On the morning of January 20, John Armstrong, the boat builder, drew a diagram in the sand of the proposed large boom. He was joined not only by Bolinas residents, but by a Standard Oil crew as well.

At a time when long-hairs were disdained by corporate America and by many in the so-called Silent Majority, something remarkable occurred: the oil company crew gave up separate efforts and began helping the locals. Standard Oil’s supervisor said “We took the approach of finding out who the [local volunteers’] leader was, then asking him how we could give him what he needed.” One Bolinas resident recalled that “you’d walk into a room and there were all these long-hairs telling guys in neckties what to do.”

Working day and night, aided by mercury-vapor lamps provided by the Army, they built a system of booms at the mouth of the lagoon: two major booms, one curving in, the other out, with smaller booms in between them, interspersed with straw. Neither the 2AM tide nor the 4PM tide, both five feet high, brought oil into the lagoon. “The system managed to fend off or contain virtually all the oil…”

Volunteers patching one of the three booms at Bolinas Lagoon, January 21, 1971 (Roy H. Williams, Oakland Tribune)

On Thursday, January 21, the SF Chronicle reported that the “status of Bolinas Lagoon, home of the blue heron and the [great] egret, was tentatively listed as ‘saved’ late yesterday, but another tide early today could change its delicate balance.”

Grebes behind the Bolinas boom (George Silk, Life Magazine of Feb.5, 1971)

Oil slicks continued to foul Marin shores. Residents and volunteers tried to clear “thick black gobs” from the rocks. At Muir Beach, another ribbon of oil twirled in tidal currents. Bolinas beaches “continued to be covered by new oil almost daily despite repeated cleaning.” A local official reported that all of Stinson Beach was “covered with thick oil. It’s gone up the beach and about 30 feet from low water.” At Duxbury Reef (outside the Lagoon) skimmers couldn’t reach the slick because the shore was so rocky.

But at the Lagoon the booms held. The Bolinas Fire Chief reported “there’s no oil in the lagoon.”

COLLECTIVE WORK TO CLEAN THE BAY

By the time dawn broke on the morning of the spill, beaches and shorelines were drenched in oil. Ultimately, oil contaminated beaches 40 miles to the south of the Golden Gate − almost to the elephant seal preserve at Año Nuevo − and 20 miles to the north. Oil landed on 149 miles of shoreline both inside and outside the bay.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that the entire Bay Area joined in the clean up effort. One participant estimated that 40,000 citizens were involved.

National Geographic later wrote:

“[N]either the company [Standard Oil] nor the government experts had foreseen the phenomenal response of the public: That such vast volunteer forces − uniting all ages and all walks of life − would spontaneously organize themselves, work tens of thousands of man-hours, and put their stamp of unstinting enthusiasm on the great cleanup.”

One observer called the effort “the Dunkirk of ecology.”

“[M]obilizing of volunteers for both rescuing birds and cleaning them, as well as….cleaning the beaches, was carried out by the citizens themselves in the traditional American manner without any direction or supervision by any established government agent. If anything, official organizations were conspicuous by their absence.”

“ ‘That first day, on Monday, they were mostly long-hairs, the hip, the ‘street people’…they responded right away. By Wednesday the ‘straight people’ had fully joined in − businessmen, bus drivers, they’d arranged to take time off. Schools let youngsters out of class to help. Some retired people out there were so old they had trouble walking on the sand. The company hired a lot of construction workers, so you saw hard-hats too. It sure was a real American cross-section.’ ”

One woman who described herself as a “hard hat’s wife” said, “After working with these longhairs, up to their necks in water and goo for 20 hours, we’ve gained nothing but respect for them.”

Volunteer with oiled straw. (Jonathan S. Blair, National Geographic, June 1971)

The Standard Oil employee supervising the company’s clean up operations told a reporter:

“You couldn’t pay a person to do this job, to go into the water the way those kids did. None complained of being cold. The only time I found one unhappy was when we couldn’t get them straw fast enough.”

The US Army provided portable mercury-vapor lamps so the work could continue through the night. The Army also dropped “straw by the ton” from helicopters. More straw was brought by dozens of boats and barges. The oil-soaked straw was picked up by cranes on barges, people in small boats using pitchforks, and volunteers on the beaches. It was loaded into dump trucks and taken to pits and landfills to decompose.

Schools closed and students and teachers went to the beaches to gather birds and clean up the shores. At Baker Beach, just west of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, 250 young people and hardhats spread hay. Surfers and skin divers in wet suits swam out to collect oiled birds floating on the water.

Project One, a recently-formed warehouse community in a former candy factory, “evolved practically overnight into an information and coordination center for the entire Bay Area.” The San Francisco Switchboard operated there, sending spotters to beaches who reported back the conditions and what was needed. They had to cope with Pacific Telephone: after not responding for over 48 hours to requests for emergency lines, the phone company finally showed up and pronounced the jerry-rigged phone system (expanded to cope with thousands of calls a day) illegal and threatened to disconnect it. Also, the SFPD began ticketing cars parked outside Project One, even though the warehouse was in an industrial area with no parking problems.

Hippies and hard-hats at Ocean Beach, with the Cliff House in the background. (Photo: Dennis O’Rorke)

Standard Oil reported it had donated trucks, cleaning materials, money, and manpower (700 hired workers). To remove oil from beaches and the ocean, Standard was using 10 tugboats, 25 specially equipped water craft, seven skimmer barges, 13 tanker trucks, 20 dump trucks, and four tractors. It provided more than 39,000 bales of hay and 2,100 pitchforks.

The major media politely refrained from mentioning that Standard Oil was obligated by a 1970 law to spend at least $4 million on clean up. The Chronicle did point out that by paying, Standard was avoiding certain fines.

Standard Oil also said it was paying the Indians occupying Alcatraz Island to clean the shoreline there, and would provide equipment. But a sinister plot began to take place as federal officials used an excuse they knew to be false − that the lack of light or a foghorn on Alcatraz had played a role in the collision − to begin secretly planning to evict the Indians. President Nixon gave the go-ahead.

Meanwhile, efforts continued at Bolinas Lagoon. On the night of Monday, January 25, volunteers finished constructing a 1,400 foot long boom made of huge logs laced together by 4x4s. This double boom had a wire mesh that extended into the water where it would trap both the oil globs and the straw absorbing them. The boom weighed three hundred pounds per foot.

But suddenly Standard Oil decided that there was no further threat of oil invading Bolinas Lagoon and withdrew its support. Standard Oil’s Philip Brubaker said the company had joined the plan a week ago, but since then the threat had diminished and the huge logs used to make the boom would be a danger to shipping and to house pilings.

John Armstrong told reporters, “We got together on a plan and half-way through it, Standard Oil backs off.”

Pierre Joske, director of the Marin County Parks Department, noting that the oil washed out but the tide brought it back in, said: “Sunday, I thought Standard Oil was right. Now, I think the kids are right.”

At first stymied by lack of equipment with which to launch the boom, locals instead used their human power. In an effort of incredible collaboration, hundreds of young people lifted the boom into place across the mouth of the lagoon.

Residents and volunteers said they would not call on Standard Oil for help anymore.

Lifting a boom. (Jonathan S. Blair, National Geographic)

BIRD RESCUE EFFORTS

By the time dawn broke on January 18, a few hours after the spill began, people had opened stations to take in oiled birds. KSAN and the San Francisco Switchboard set up an information center to coordinate the massive response by people wanting to help.

The Richmond Bird Care Center, set up in a warehouse owned by the University of California and operated by volunteers with the help of veterinarians, opened at 8AM on January 19. About 200 people arrived to prepare the warehouse to receive birds; an “incredible amount of activity and cooperative effort.” The first bird arrived there at 4PM, then came the rush as 300 birds arrived throughout the night. Hundreds more came in the next day and night and even six weeks later birds were arriving and volunteers were putting in 10 to 15 hour days and sleeping near the birds.

From San Francisco Good Times newspaper, January 22, 1971. (Photo by Gary Freedman)

At least 30 other centers had opened on the night of the 18th and on the 19th. One “official” bird cleaning facility was the basement of the lion house at the San Francisco zoo. Later this facility was closed because the roaring of the lions frightened the already-traumatized birds.

The local newspapers ran daily information boxes on where to go to help. Donations came from local corporations. Granny Goose sent cornmeal (used to clean the birds). Weyerhauser donated cardboard boxes. A pharmacy gave a 55-gallon drum of mineral oil. Shakey’s donated pizza for volunteers. “Sailors from the USS Neptune ‘liberated’ medical supplies.”

Richmond Center tally board. (Jonathan S. Blair, National Geographic)

KSAN printed leaflets with directions on how to pick up the oiled birds and how to clean them, but there was no official organization and few people had any experience. Furthermore, at that time, there were no established, proven methods for removing oil from birds. Even if the oil was safely removed, rescued birds would likely die of starvation, hypothermia, dehydration, or exhaustion. Those birds that survived the initial trauma had to be kept and fed for several months until new feathers replaced the cleaned feathers that had lost the ability to repel water.

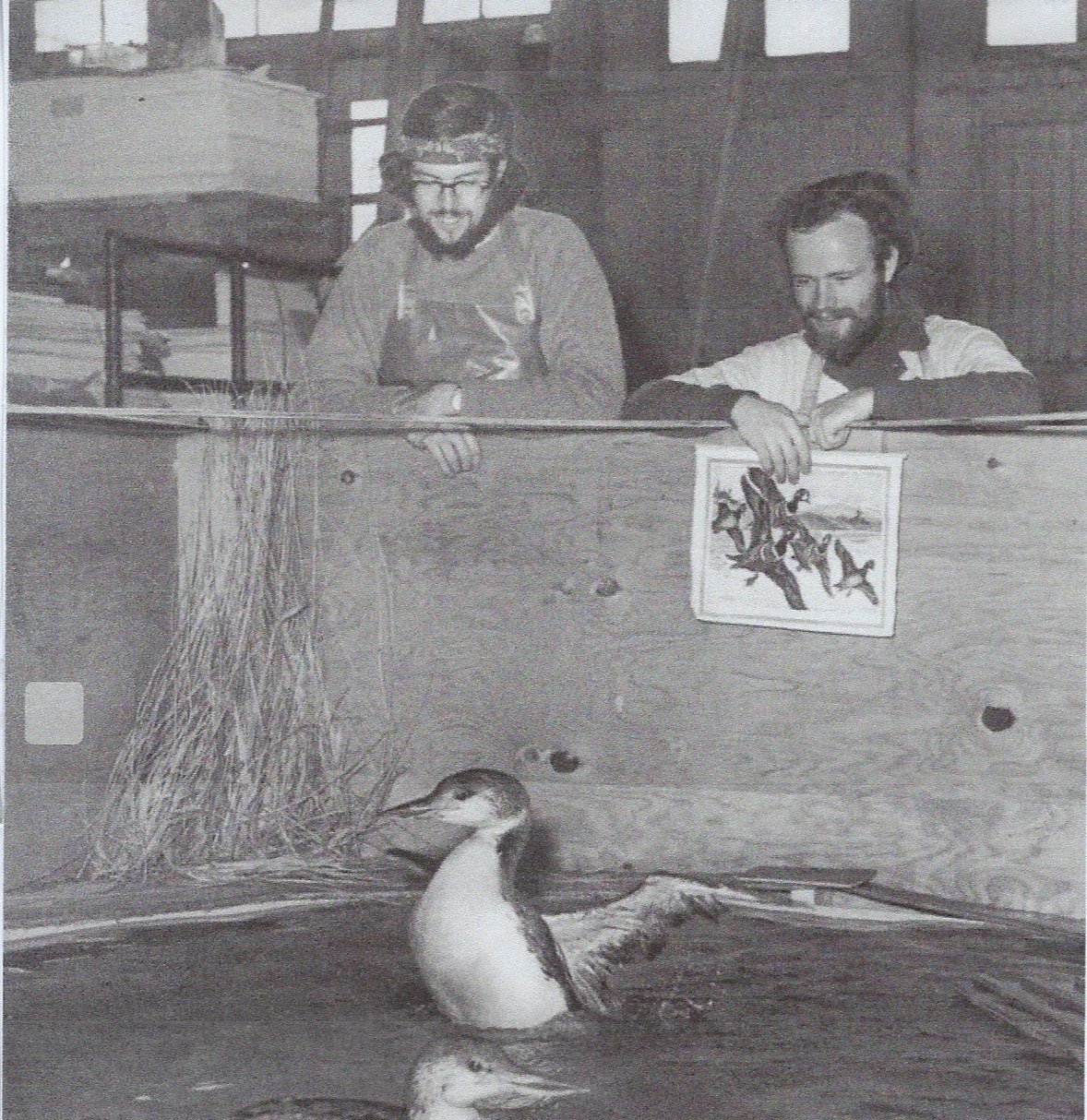

Participants and observers noted that birds taken to the Richmond rescue center had a much higher survival rate of 30%, compared to 3% at the zoo center. The Richmond center was staffed mostly by counterculture people who took extraordinary care of the birds. For instance, the “experts” at the zoo and other centers, hired by Standard Oil and various government agencies, held oiled birds, who were already traumatized, by the feet and dunked them head-first into the cleaning solution. At Richmond, each bird was painstakingly cleaned by hand by two or three people. They watched the birds carefully and shared their observations, learning what size pens each species needed, the maximum number of other birds in the same pen, and so on.

Berkeley Tribe newspaper, Jan 22, 1971 (photo by KW)

Volunteers continued working for weeks, still putting in twelve or fifteen hours a day and sleeping in the warehouse in Richmond. An article reported 75 volunteers caring for the birds on a 24-hour basis.

Two birds recovering at the Richmond rescue center on February 10, 1971. (Photo: Bud Wakeland, Oakland Tribune)

Ultimately only a few hundred birds were saved out of thousands taken in to be cleaned. One volunteer wrote, “Most were the sturdy surly sea ducks: scoters and scaups. Only a few grebes. No loons made it.”

Dr. James Naviaux, founder of the National Wildlife Health Foundation, projected that less than 5% of the more than 4,000 rescued birds survived. Another 1,100 bird carcasses were collected from beaches. The California Department of Fish and Game estimated 7,000 bird deaths, but a scientific study believes that a minimum of 20,000 birds died.

The true total will never be known.

OTHER EFFECTS

“Distribution of oil slicks (shown in hatchings)…resulting from the 18 January 1971 oil spill.” (Smail, et al., in California Birds, Vol.3,No.2, 1972)

Aerial surveillance on January 21 from the newly-formed EPA reported that “the oil had penetrated a larger area than previously indicated.” The oil slick outside the Golden Gate had doubled in size. Oil had spread deep into the bay; four large streaks were found south of the Bay Bridge. Heavy concentrations were seen on the coasts of Marin and San Mateo Counties and in the Tiburon peninsula.

That same day Standard Oil announced that 336,000 of the 840,000 gallons had been captured from water and beaches.

The next day, most of the “missing 500,000 gallons” was located. The Coast Guard reported that it had “been churned into an emulsified seawater cocktail and is now boiling in sub-surface currents” outside the Golden Gate where it was expected to be eventually eaten by natural bacteria. A State Fish and Game spokesman said that fish would avoid the oil.

But Dungeness crabs could not avoid it.

Life Magazine, February 5, 1971

In the fall young crabs crawl along the bottom of San Francisco Bay through the Golden Gate and back to where they were born, twenty or so miles out in the Pacific Ocean. There, over the next few years, they grow to their full size.

The Dungeness crab population in the oil spill area collapsed after the spill and the season’s catch was 70% less than what it had been in the 1969-70 season.

Also severely affected were mussels, barnacles, limpets, sea anemones, and the grasses and plants that sea animals needed. The Bodega Marine Laboratory noted that “no one really knows much about the effects of oil on the microscopic plants and animals that make up the first steps in the food chain.” For one example, if the mussels were killed by the oil, starfish would starve to death. And the greatest damage had been done to the mussel beds, the largest in North America.

“Shore contamination was especially heavy along the rocky southern coast of Marin County,” and into early February small quantities of oil were coming into shore near Bolinas. Dr. Gordon Chan stated that if not for the efforts of the Bolinas community, there would have been an ecological disaster for the Lagoon, “particularly in the clam populations.” A government report estimated that “five million marine invertebrates, primarily barnacles, were smothered by the oil in intertidal areas of Sausalito and Duxbury Reef” alone, and that 25% of them died. Limpets also had a high mortality, but rebounded within five years as did other marine invertebrates.

“Seven million marine organisms” were killed.

PROTESTS

While the majority of people responded by rushing to the beaches and coastline, others engaged in protest. On January 19, at Standard Oil’s HQ in downtown San Francisco, people hurled dead fish into the building, dumped crank case oil into the ornamental pond, and spray-painted “Standard Destroys” and “Ecology grows out of the barrel of a gun” on the building. Several Standard Oil employees on their way to work that morning “scuffled briefly” with the six men and one woman, who left without being arrested or, as the Chronicle phrased it, “the vandals escaped.”

On Friday, January 22, U.C. Berkeley students demonstrated at Sproul Plaza and played a message from Nobel Laureate Linus Pauling that America’s excessive energy use was promoted by the oil companies for their profits. “We’re robbing our children and our grandchildren of what should be their heritage.” Sierra Club president Phil Berry said that “Standard Oil has the worst environmental record of any oil company in the world, and that’s saying something.”

On Saturday, January 23, several hundred people held a protest rally in front of Standard Oil’s Richmond refinery and draped dead birds on the front doors.

FoundSF website. Photo by Howard Harrison

The Earth Army called for a “trial of Standard Oil” on Wednesday, January 27, outside Standard’s San Francisco HQ. “Bring evidence of crimes against the environment,” said the announcement. “The purpose of the demonstration is to emphasize that the oil spill was not an isolated event, but rather an inevitable occurrence, given the way Standard goes about its business.”

About 1,500 people gathered and found the company guilty. Several hundred people then marched to the South Vietnamese embassy a few blocks away. One poster read “Oil here, napalm there.”

That day, Standard Oil of California announced profits of over $5 billion for fiscal year 1970.

AFTERMATH

LEGAL REPERCUSSIONS

On February 20, the Coast Guard ordered a formal hearing into the causes of the disaster. The Sierra Club’s request to participate fully in the hearing as a party of interest was denied.

In March 1971 the Coast Guard filed negligence charges against the skippers of the Arizona and the Oregon.

The Coast Guard released a report on August 1, 1971 that found the collision had been avoidable, caused by “failure or inadequacy of four different systems or subsystems….” and recommended legislation requiring certain communication equipment and radar on all vessels, and revocation and suspension of the licenses of the masters of both ships.

On October 27, 1971, Standard Oil and the Chevron Shipping Company were indicted under the Refuse Act of 1899 by US Attorney James Browning.

Jonathan S. Blair, National Geographic

Two lawsuits were filed on January 20, 1971, seeking over $3.5 billion in damages. In one, a resident of Stinson Beach and a person who kept a boat in Marin filed a class action suit on behalf of property and boat owners. The second was a class action on behalf of boat owners in the area, seeking $2,000 damage for each of 4,800 boats. These two cases were dismissed by Judge Ira Brown on Dec. 11, 1971. In a ruling that defied common sense and benefited Standard Oil to a staggering degree, Brown told plaintiffs that class actions were impractical and each person harmed should sue Standard Oil individually.

The local underground newspapers urged people to file claims for their expenses in cleaning the beaches and birds.

POLITICAL REACTIONS

On February 8 and 9, Hon. John Dingell (D, Mich) chaired a Special Subcommittee of the Congressional Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries that held hearings in San Francisco, in part to add information concerning two bills that initiated strict measures to prevent collisions and accidents, as well as to investigate the spill and responses to it. The Subcommittee took evidence from Standard Oil, the Coast Guard and various other agencies, scientists, and many of the volunteers.

Because of the widespread outrage and the massive community response to the 1971 spill, politicians could not issue proclamations and then go back to business as usual. Many of the environmental protections and most of the legislation that exist today came into being the year after the San Francisco oil spill and a few years after the 1969 Santa Barbara oil well blowout.

−On Jan 20, 1971, the president of the SF Bar Pilots Association urged a law requiring that every ship entering or leaving a California port have a pilot on board: “…in the 12 year history of the Pilots’ Association, there has never been a serious accident involving two ships when each of the ships had a pilot on board.” The proposal became law.

Bolinas shorebirds. (Marin County Parks Department photo)

−In 1972 Congress passed the National Marine Sanctuaries Act, authorizing the creation of sanctuaries to protect the waters and to secure habitats. In 1981, the Greater Farallones Marine Sanctuary was designated. Bolinas Lagoon is in the protected area. The Sanctuary encompasses over 120 miles of the California coast. Originally 1,279 square miles, it was later expanded to 3,295. Off shore oil drilling is permanently banned in the Sanctuary.

−The Marine Mammal Protection Act was signed into law Oct 21, 1972.

−The Ports & Waterways Safety Act of 1972 gave the government authority to regulate tanker design and operating procedures and to regulate all types of dangerous substances on piers; expanded ship inspection programs; and financed the Coast Guard’s Harbor Advisory Radar Project. While signing the bill, President Nixon said the intent was to prevent recurrence of such “ecological tragedies like the tanker collision which dumped over half a million gallons of oil into San Francisco Bay early last year.”

−The Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972 (renamed the Clean Water Act) called for Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasures regulations. Nixon vetoed this act, but Congress overrode the veto.

On May 24, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Clean Water Act protects connected bodies of water, but not adjacent wetlands that don’t have a continuous visible surface connection; therefore no federal review is necessary when a property owner plans to develop or, as in this dispute, dump sand and gravel into wetlands. Michael S. Regan, the EPA Administrator, issued a statement expressing disappointment and affirming the EPA’s commitment to “ensuring that all people, regardless of race, the money in their pocket, or community they live in, have access to clean, safe water. We will never waiver from that responsibility.”

Bolinas, seen from Mount Tamalpais, Bolinas Ridge Trail, April 2013 (Author photo)

−In 1973, the Endangered Species Act passed Congress overwhelmingly. This law “has prevented the extinction of some 291 species” and was recently hailed as “one of the most important foundational conservation laws in the country.”

−In 1973, because of the 1971 spill, the Coast Guard implemented the vessel traffic system, a way to monitor where ships are and where they plan to go. The system uses radar, cameras, and civilian and military controllers. By 2001, the system was being used along all U.S. coastlines.

−The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 was passed after the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989, setting a deadline of January 1, 2015 for all tankers to be double hulled. (However, there’s no such requirement for container ships or other vessels, and in November 2007 a container ship, the Cosco Busan, rammed into the Bay Bridge and spilled over 53,000 gallons of used bunker fuel into the bay.)

Farallon birds. (Dave, Flickr)

−In 1972 Californians used their citizen initiative power to create the California Coastal Commission with a mission to “preserve, protect, and where possible restore” the shores.

−Part of Audubon Canyon Ranch was renamed “Volunteer Canyon” to honor the work of volunteers to protect the Lagoon.

−Point Reyes National Seashore was officially established by the Department of the Interior on Oct 20, 1972.

BIRD RESCUE

In April 1971, a few months after the spill, International Bird Rescue Research Center was incorporated as a non-profit organization, founded by volunteers who had worked on rescuing the birds in January, with the purpose of developing effective means of treatment. Now named International Bird Rescue, it is the primary bird rescue group in the world and has worked on 225 spills and other disasters. It has rescued and saved the lives of thousands of birds after oil spills.

International Bird Rescue founder Alice Berkner training volunteers on cleaning oiled birds. (International Bird Rescue photo)

International Bird Rescue rehabilitated and released over 40% of oiled birds in eight small spills in California in the 1980s, incorporating lessons learned during the 1971 spill. After the Exxon Valdez disaster, the state of California established the Oiled Wildlife Care Network. 26 rehabilitation centers, including two new ones for the IBR, were built on the west coast, administered by the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. Between the OWCN’s inception in 1994 and 2003, over four thousand birds were recovered and rehabilitated with a release rate of 60 – 75%.

Among its work, IBR saved 90% of 20,000 oiled African penguins after the “Treasure Spill” near Cape Town in 2000. During 2010 the Deepwater Horizon disaster, International Bird Rescue teamed up with several other rescue groups to capture 8,000 oiled birds (including dead birds) and released 1,246 after rehabilitation.

BOLINAS

G. Irons and T Vetch, Deviant Slice Comics, 1972

The 1971 disaster “indelibly changed the character of West Marin’s towns and residents…[and turned] a quiet, somewhat complacent area into a bastion of progressive land-use politics and radical ideas” as “enthusiasm from the cleanup effort surged over into local politics.”

Several large scale development projects were being planned before the oil spill, including a proposal to link Stinson Beach and Bolinas into one sewer system that would allow huge population increases, up to ten thousand. Bolinas residents, some of whom who had settled in town after working on the clean up, threw out two directors of the Bolinas Public Utilities District by a recall vote, ran a slate that won four seats on the five-person board, and set about drafting a new community plan. The new BPUD then passed an ordinance prohibiting new water hookups, thus preventing construction of more houses. The number of water meters in Bolinas was frozen for nearly 40 years.

New board member Orville Schell wrote that “We became the first town in America that we know of to have a zero-growth control limitation.”

But by 2005, many of the 1971 residents were gone. Long-time residents who had lived alternative lifestyles that required little money had been displaced by tech industry millionaires. Before the internet, people who worked in the cities didn’t live in Bolinas because of the long drive (at least 75 minutes to downtown San Francisco). Telecommuting removed that impediment. And GPS made Bolinas easy to find, even without road signs.

In 2005 a water meter was auctioned by the town for $310,000. By 2019, the average home price in Bolinas had risen to $2.5 million.

But other preservations have endured.

West Marin farm. (photo: Jetsettimes.com)

In 1971 residents of West Marin, inspired by Bolinas, formed their own coalition, the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin. One of its accomplishments was to restrict houses to one per 60 acres.

In 1980 a farmer and an environmentalist united to form the Marin Agricultural Land Trust to protect farming from development. It was the first farmland trust in the United States and the pioneering use of conservation easements — 93 thus far — is a method that’s been replicated all over the country to save small farms. MALT has protected 55,000 acres as farmland or forest in the northern Bay Area. To this day, West Marin is mostly rural, a landscape of hills rolling toward the Pacific Ocean dotted with several small farms: dairy cows, free range beef cattle, sheep and wool production, fruits and vegetables.

Also inspired by Bolinas, the small town of Lagunitas stopped a planned freeway through the scenic rural valley. And residents of Point Reyes Station created a community plan to preserve the character of their town.

Some people have bitterly complained that growth restrictions make it almost impossible to find and afford housing in Marin County. Preservation of land and restrictions on building do usually lead to high housing prices, which is certainly true in Marin, where the natural beauty (kept beautiful, thanks to building restrictions) makes it a desirable place to live. But the alternative of allowing development wherever and whenever developers want is disastrous. One need only look south in California to see the results of unchecked “growth.” Thousands of houses crowd against fire-prone forests, the increased need for water has turned rivers into trickles and drained aquifers, and fertile farm land has been permanently taken out of production; and because the developments are necessarily farther from the cities, people spend hours commuting every day, compromising air quality, not to mention quality of life.

But are “no growth” or “unchecked growth” the only choices? Why not an approach that utilizes already-developed land? For instance, inner city housing that’s deteriorated and empty, offices that aren’t being used, abandoned malls and warehouses, could be transformed, and have been in some places.

Currently there are sixteen million vacant houses in the United States. Citizen action, with region-wide planning and national support, could turn neglected areas into thriving communities.

WHAT IS TO BE DONE?

As disastrous as the 1971 oil spill was, it might have been shrugged off as just another unfortunate but inevitable event − but for the massive response of the people. After the spill, a major shift occurred in the attitude of Americans regarding the environment. A poll in May 1969 reported that only 1% of Americans thought protecting the environment was important. But in May 1971, four months after the oil spill, 25% of Americans thought so. A Harris Poll in October 1971 reported that 78% of the public was willing to pay for clean up of air and water pollution.

In 2023 our planet is in more trouble than ever, and more people than ever think protecting the environment is important. But now there is no mass movement in our country. Senator Gaylord Nelson hadn’t thought “that a one-day demonstration would convince people of the need to protect the environment” and believed that “Earth Day was to be the catalyst” for a continuing national drive to set new priorities. But instead, as historian Adam Rome points out, Earth Day now resembles a trade show where the latest green goods are sold and children are encouraged to plant trees and collect litter.

In 1971 people

“consciously defined themselves as a part of the community, consciously decided on collective action, went down to the beaches, went to bird cleaning stations, came out after hearing what went over the air of KSAN, came out deliberately in a situation where the majority of the community seemed to say, oh, let the Fish and Game Department do it; let the zoo do it; let Standard Oil do it. These people consciously determined to do it.”

In the fifty-two years since the 1971 spill, law enforcement agencies have adopted an air of exclusivity and promote an “us against them” attitude. “Crowd control,” that hallmark of modern policing, has become the overriding concern in a crisis. Police, FBI agents, park rangers, and others with quasi-law enforcement status seem to enjoy exerting their authority and maintaining that only “experts” should be involved. The rest of us should sit back and do nothing. “The best thing you can do,” people are routinely advised, “is go home and stay there.”

Cleaning Agate Beach in Bolinas on January 21, 1971 (photo: Roy H. Williams, Oakland Tribune)

The perspective that only government-sanctioned authorities can deal with crises has become ingrained in most of the citizenry. That, along with the not-unreasonable fear of being sued, has created an increasingly passive and submissive public. People often decide not to get involved, beyond taking cell phone videos (which of course can be extremely helpful). Certainly there are areas where people take action to improve their neighborhood − start a community garden, put on block parties or craft fairs, or even fight specific irresponsible development proposals − but these actions rarely evolve into enduring movements aiming for deep changes.

One advantage we have now is the ability to communicate almost instantly. But communication is only the first step. Sending messages and slogans on social media are the means of organizing, but too often are taken to be the ends.

We have become a nation of individuals. Collective action is viewed with suspicion and, except for the occasional demonstration, rarely undertaken; and after the largest demonstrations, participants go home feeling that something has been accomplished and they can return to their normal lives.

The response of the community to the 1971 oil spill and the people’s determination and persistence despite threats of arrest and corporate impediments show us the importance of collective action in catastrophes.

Front pages of two underground newspapers January 1971.

The civil rights and anti-war movements in the 1960s and early 1970s were multi-faceted. Of course many people did little more than attend demonstrations, but the activists devoted their lives to the cause. They published newspapers and started radio stations. They created food co-ops, mechanic shops, carpentry collectives, medical clinics, and so much more. They lived in communes, shared expenses, and shunned luxuries; their low cost of living freed them from having to work regular jobs, so they could devote themselves entirely to the movement.

This was a mass movement. Fighting racism and opposing the war were the focal points, but the movement was inextricably entwined with struggles for prisoners’ rights, GI rights, trade unions, student empowerment, the environment, feminism, and more.

And although this aspect of the movement is rarely mentioned today, it was anti-capitalist.

As long as the economy is driven by the profit motive, planet earth will suffer the consequences. Corporations make larger profits by ignoring or skirting or outright violating laws meant to curtail pollution. American’s unions have been essentially destroyed; and because pensions have been replaced by 401Ks, workers have an interest in keeping corporate profits high. Capitalists constantly call for “growth,” which entails everything from building housing developments in fire country, to opening new coal-fired power stations, to drilling for oil in the Alaskan wilderness, to destroying the Amazon in favor of agribusiness.

The suicidal mania for wealth is worse now than ever, and it’s making the planet inhospitable for humans and other living beings.

While driving an electric car or eating a vegan diet are commendable practices, they won’t solve the planetary crisis. Scrupulous individual actions cannot replace the urgent need for a mass movement.

Poster produced by the San Francisco Good Times newspaper.