The Death of Ernest Hemingway

Conventional wisdom asserts that Ernest Hemingway committed suicide due to inherited insanity. Hemingway may have pulled the trigger himself, although it cannot be ruled out that someone else did.

But if he shot himself, he’d been driven to it. His brain had been damaged by more than twenty electric shock treatments administered by a doctor who was reporting on Hemingway to the FBI. The electric shock destroyed his memory. He could no longer write.

Hemingway’s suicide wasn’t necessarily the goal; perhaps it would have been enough to render him too incapacitated to speak or write intelligibly, or for him to be discredited as mentally unstable.

Who wanted to extinguish America’s most revered writer, and why?

* * * *

KEY WEST AND SPAIN

In late 1940 Hemingway’s novel For Whom the Bell Tolls was published. Over a year before the U.S. entered WWII, the novel illustrated the critical importance of fighting fascism. It also portrayed the Spanish Republic as doomed by anarchism and argued the necessity of adhering to the discipline of Communism − even if one didn’t agree with it ideologically − to defeat fascism in Spain. The novel highlighted the lack of support for the Spanish Republic from any country other than the Soviet Union.

For Whom the Bell Tolls was an immediate best seller.

For citations to all facts and quotations, see Notes & Sources to The Death of Hemingway https://www.necessarystorms.com/home/notes-and-sources-to-the-death-of-ernest-hemingway

This novel and Ernest Hemingway’s participation in the defense of the Spanish Republic weren’t his first radical acts.

Douglas Wolcott Reynolds, “Labor Day Hurricane, Florida Keys, September 4, 1935.” Reynolds was a member of the CCC Company 1421 sent to rescue and recover. The painting was made from a photograph in the Miami Tribune. (Smithsonian American Art Museum, transferred from General Services Administration.)

In September 1935, Hemingway was in Key West when a powerful hurricane struck, with 185-mile-per-hour winds and a 17-foot tidal wave. When it stopped he rushed to the hardest-hit Keys in a boat, bringing provisions. But the camps of over 700 World War I veterans working on construction projects had vanished. Hemingway made five trips and found “nothing but dead men.” Bodies were floating in the ocean and decomposing in the sun. Hemingway hadn’t seen such death and destruction since the battlefields of WWI. He took photographs of some of the 458 people who had died, then wrote a searing indictment of the FDR administration.

“Who Murdered the Vets?” was the cover story of the September 17, 1935 issue of The New Masses.

Those veterans were some of the thousands of World War I soldiers who had been promised bonuses that could not be redeemed until 1945. In May 1932, as Depression gripped the country, veterans marched on Washington DC to demand payment of the bonuses from President Hoover. They set up a Hooverville, the nickname of tent cities and shanty towns across the country during the Depression. The Bonus Army Hooverville was the largest in the country. 32,000 residents (17,000 of whom were veterans) lived in 26 camps, with 15,000 in the main camp. The camps were run in an orderly fashion and had a barber shop, library, school, newspaper, and vaudeville shows. Food and supplies were donated by the Bonus Army’s many supporters.

And − unlike the rest of Washington DC − the settlement was completely racially integrated. Roy Wilkins wrote in the NAACP magazine that there was one absentee in the Bonus Army: James Crow.

The local chief of police was supportive, visiting daily, bringing food and arranging for doctors to come twice a day. Meanwhile J. Edgar Hoover tried to establish that the Bonus Army had communist roots.

On July 28, President Hoover ordered the settlement destroyed. General MacArthur attacked with machine guns, grenades, tear gas and infantrymen armed with fixed bayonets, and “for the first time in the nation’s history, tanks rolled through the streets of the capital.” The tanks were commanded by Major George Patton. At least two men were killed and over 1,000 people were injured. Grenades started fires and burned whatever shanties had not been flattened by tanks.

Bonus Army camp being burned in Washington DC, with the Capitol in the background. (Photo: Signal Corps/National Archives)

When newsreel accounts were shown in movie theaters across the country, audiences booed President Hoover and General MacArthur. Hoover lost the election that year, at least in part because of his assault on the Bonus Army.

After Franklin Roosevelt’s inauguration in January 1933 the veterans held another Bonus March. FDR also refused to pay the bonuses, and instead offered the men jobs in New Deal programs such as the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps).

One thousand of those Bonus Marchers were sent to a work project in the Florida Keys, “where they can’t make trouble,” wrote Hemingway (who’d driven an ambulance and been badly injured in WWI) to do “coolie labor” during hurricane season. “Wealthy people, yachtsmen, fishermen such as President Hoover and President Roosevelt, do not come to the Florida Keys in hurricane months.” Yet FDR sent the vets there to live in flimsy wooden and cardboard shacks. “Whom did they annoy and to whom was their possible presence a political danger?” asked Hemingway. “And who failed to evacuate them when evacuation was their only possible protection?”

The article concluded:

All cars except the engine of the Florida East Coast Emergency Relief train derailed in the nearly 200 mph winds as the rescue train headed for Matecumbe in the Florida Keys. (Photo: Florida State Library & Archives General Collection; Image No. N041488)

“You’re dead now, brother, but who left you there in the hurricane months on the Keys, where a thousand men died before you in the hurricane months when they were building the road that’s now washed out? Who left you there? And what’s the punishment for manslaughter now?”

The article was reprinted in the Daily Worker (the Communist Party’s newspaper) and quoted in Time Magazine.

In January 1936, the Senate overrode FDR’s veto and passed a law authorizing immediate payment of the bonuses.

The Spanish Civil War began in summer of 1936. During 1937 and 1938 Hemingway made four trips to Spain as a war correspondent, film maker, playwright, militia instructor, and armed combatant. He passionately supported the Spanish Republic. In June 1937 he was the featured speaker at the American Writers Conference, and said:

“There is only one form of government that cannot produce good writers, and that system is fascism. For fascism is a lie told by bullies. A writer who will not lie cannot live and work under fascism.”

In July 1937 Martha Gellhorn, who would become Hemingway’s third wife, arranged for Hemingway and Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens to go to the White House to show their movie about the Spanish Civil War to Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt. Both Roosevelts liked “The Spanish Earth” immensely, and FDR even said they thought it should include more propaganda. But FDR spoke so much that Hemingway and Ivens were unable to present their argument that the arms embargo on the Spanish Republic be lifted.

Overwhelmed by fascist forces, the last Republican defenders surrendered on April 1, 1939. Franco ruled Spain as dictator until his death in 1975.

Hemingway (center) in Spain in 1937, with Ilya Ehrenburg, a Soviet journalist, and Gustave Regler, a German Communist. (Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection, JFK Presidential Library & Museum, Boston.)

At the end of 1940, with money earned from For Whom the Bell Tolls, Hemingway and Martha bought a house in Cuba, La Finca Vigia. He would live there longer than any other place in his life − 21 years.

That year he signed a letter opposing the FBI’s arrest of Detroit citizens accused of violating the Neutrality Act by having encouraged enlistments for the Spanish Republican cause. Two years later, when the FBI officially opened a file on Hemingway, this letter was cited:

“When the Bureau was attacked early in 1940 as a result of the arrests in Detroit…Mr. HEMINGWAY was among the signers of a declaration which severely criticized the Bureau in that case.”

Another 1942 memo to J. Edgar Hoover stated:

“Hemingway, it will be recalled, joined in attacking the Bureau in 1940, at the time of the ‘general smear campaign’ following the arrests of certain individuals in Detroit…”

Hemingway was a “premature anti-fascist,” a term (possibly invented by J. Edgar Hoover) used for the Americans who fought for the Spanish Republic and against fascism before the U.S. government joined the battle. All the “premature anti-fascists” were subjected to years of FBI surveillance and harassment.

In April 1941, the Pulitzer Prize Committee unanimously voted For Whom the Bell Tolls the best American novel of 1940. But it did not receive the Pulitzer Prize. Nicholas Butler Murray, the fascist-sympathizer president of Columbia University (which administers the Pulitzer), vetoed the nomination; the book was “obscene, vulgar, and revolting.” No Pulitzer for literature was awarded that year.

In Europe one country after another fell to the Nazis. Britain and the Soviet Union put up strong resistance; the armed forces and the citizens of both countries suffered severely. The United States finally entered the war after Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941.

Too old to be a soldier, Hemingway came up with other ways to fight the Nazis.

THE CROOK FACTORY, OPERATION FRIENDLESS, AND THE F.B.I.

In May 1942, at the instigation and authorization of the U.S. Ambassador to Cuba, Spruille Braden, Hemingway organized a crew of 26, many of them in exile from the Franco regime, into a group he called the “Crook Factory.” Their purpose: to engage in counter-intelligence of fascists in Cuba.

The Crook Factory recruits came mostly from the anti-fascist Basque Club of Havana, and included jai alai players, former bullfighters, a Catholic priest who’d been a Loyalist machine gunner, waiters, Cuban fishermen, Spanish noblemen in exile, and assorted “wharf rats and bums.” They began operating in September 1942 with a monthly budget of $500 paid by the Embassy. Headquarters was at La Finca Vigia, where meetings were held and operatives reported information. Hemingway stayed up through the night writing reports, then drove 12 miles to deliver them to Robert Joyce, the Second Secretary of the Embassy, who had been placed in charge of the Embassy’s intelligence activities.

Hemingway detractors have ridiculed both the effort and the need. The detractors are wrong on both accounts.

Of the 300,000 Spaniards then living in Cuba, an estimated 30,000 were “dedicated Falangists” (Spanish fascists) who were active and dangerous to American interests, according to Ambassador Braden. Cuba had deep historical ties with Spain and many Cubans were sympathetic to fascism, including the owner-editor of Havana’s most influential newspaper. Ambassador Braden “documented the Spanish Embassy’s clandestine support of the Falange” and the possibility that Falangists in Cuba were gathering information on military preparations, refueling German U-boats, and engaging in sabotage.

Meanwhile, the German spy agency Abwehr snuck spies into Cuba as well as into the United States. Hemingway biographer Carlos Baker notes that “the arrival of foreign spies [in Cuba] was especially dangerous because of…German submarines” then preying upon tankers and cargo ships in the Caribbean. The Cuban Bureau of Investigation made 50 arrests for espionage in April 1942. Two German spies were put on trial in September, and one got a death sentence.

In July 1942, the FBI assigned Raymond G. Leddy to Havana as the attaché (and the FBI’s Special Agent) to the Embassy. (Leddy’s curriculum vitae is included in the notes to this section.)

Shortly after Leddy’s arrival, Hemingway introduced him, at a jai alai match, as a member of the American Gestapo. That remark infuriated Leddy and the FBI, and was cited in Hemingway’s FBI file for years to come.

The first document in the file is Leddy’s memo of October 8 to J. Edgar Hoover. Leddy informed the Director of the arrangement Hemingway had with the Ambassador, and expressed concern because of Hemingway’s Gestapo remark and his having signed the 1940 protest over arrests of Spanish Civil War recruits.

Evidently the FBI was watching Hemingway before that October 8 memo. In December 1942 Hoover wrote that Hemingway’s judgment was questionable “if his sobriety is the same as it was years ago.” (Emphasis supplied.)

Within a short time Leddy warned FBI headquarters that Hemingway might expose “corruption in the Cuban government.” This prospect alarmed Leddy; he was “quite concerned” that Hemingway’s activities would be “very embarrassing unless something is done to put a stop to them.”

Leddy’s FBI supervisor told Hoover of Leddy’s concerns and suggestions, which included pointing out to Ambassador Braden

“…the extreme danger of having some informant [against Nazis] like Hemingway given free rein to stir up trouble such as that which will undoubtedly ensue if this situation continues….Leddy can handle this situation with the Ambassador so that Hemingway’s services as an informant will be completely discontinued. Mr. Leddy…can point out to the Ambassador that Hemingway is going further than just an informant; that he is actually branching out into an investigative organization of his own which is not subject to any control whatsoever.”

Two days later Hoover replied that the FBI would do nothing, noting that Ambassador Braden was “somewhat hot-headed” and would immediately tell Hemingway of FBI objections. Hoover also noted that Hemingway had ties to the White House.

However, Hoover sanctioned Leddy’s wish to discredit Hemingway. Hoover wrote to Leddy that “any information…relating to the unreliability of Ernest Hemingway as an informant may discreetly be brought to the attention of the Ambassador.”

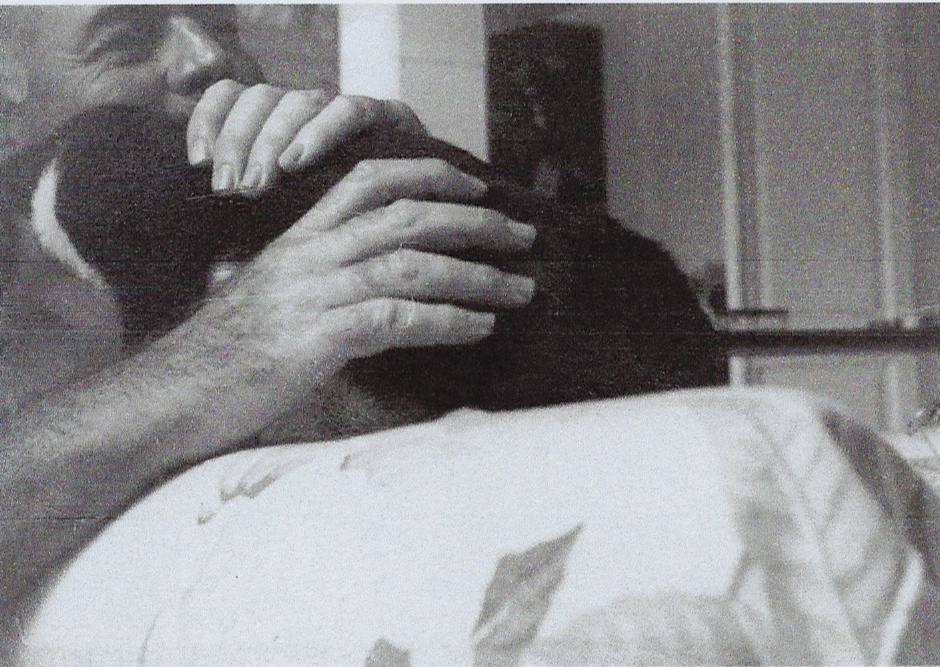

Hemingway with one of his favorite cats, Boise, at La Finca Vigia. Boise appeared (by his own name) in Hemingway’s posthumously published novel, Islands in the Stream, which was set mostly in World War II and included vivid scenes of submarine hunting. (Photo Credit: Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collections. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.)

In late 1942 Hemingway enlisted a trusted friend to take over coordination of the Crook Factory, although several incidents show that he kept active in its operations.

In December, a week before Cuban president Batista and Ambassador Braden were to go to Washington, Hemingway warned that General Benitez, Chief of the Cuban National Police, was making plans for a coup in their absence. Leddy claimed to investigate and to have found no such preparations; “the danger of alienating police cooperation by this type of report was also pointed out to Mr. Joyce [head of Embassy’s intelligence].” But a few months later, Ambassador Braden learned of a plot by Benitez and other officers to seize the presidency. The plot was foiled.

Also in December 1942, Hemingway reported to the Embassy that an Italian fascist leader interned at a Cuban hospital for medical treatment was not actually ill but had paid off Chief Benitez, and that FBI agent Leddy had taken the police chief at his word without investigation. Subsequently Hemingway notified the Embassy that the Italian fascist had attended a luncheon honoring a Spanish diplomat. Ambassador Braden was greatly disturbed and asked Leddy to investigate. Leddy said he found no evidence that the Italian had attended the luncheon. The FBI memo reported that Hemingway wanted to see the FBI’s proof of that. The FBI’s response was not recorded.

On February 10, 1943 Hemingway wrote a detailed report to Ambassador Braden explaining why the new assistant legal attaché, FBI agent Ed Knoblaugh, was “unsuited” to investigate Falangist activity, since he was likely a Falangist sympathizer. Raymond Leddy opposed transferring Knoblaugh. More importantly, he was outraged.

Knoblaugh, in fact, was a Falangist sympathizer, or at the least an apologist.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, Knoblaugh was the head of the Associated Press office in Madrid. He covered the Nationalist (Falangist) side of the conflict, and later wrote a book, Correspondent in Spain, which provided much compelling evidence for Hemingway’s objections. For example, Knoblaugh promoted the false claim that most of the damage to Guernica had not been from German bombs but had been caused by Republicans themselves, and backed up his claim by citing a joint statement of news correspondents. But “this ‘joint statement’ never existed.” Nevertheless, Knoblaugh’s “view eventually became gospel among conservative American Catholics.” Worse than that, Knoblaugh’s claim gave Secretary of State Hull an excuse for continuing America’s embargo on weapons to the Republic. Knoblaugh proclaimed that the bombing of Guernica was fortunate propaganda for the Republic; he also stated, perhaps not aware of being inconsistent, that the bombing was justified because the town “was used as a Loyalist military base” and was “in the path of Franco’s march on Bilbao.”

The ruins of Guernica. April 26, 1937 was a market day. German and Italian bombers dropped explosives that crushed buildings followed by incendiaries burning at 2500 degrees, a prelude to the carpet bombing of European cities a few years later in WWII. (Photo: taken by AP; UIG/Getty Images)

The Crook Factory work was terminated in April 1943. Agent Leddy proclaimed Hemingway’s efforts as worthless. (One author points out the contradiction in the FBI’s position: Hemingway’s work could not be both useless and problematic.)

In fact, Ambassador Braden recommended Hemingway for a decoration. Years later, Braden wrote that Hemingway “built up an excellent organization and did an A-One job.” Hemingway’s information was “accurate, carefully checked and rechecked, and [proved] of real value.”

Hemingway biographer Jeffrey Meyers writes that the FBI had seen the Crook Factory “as a rival company and wanted to put it out of business…Hemingway was at the height of his reputation…the more famous he was, the more dangerous he seemed to the FBI. Almost any other American citizen would have been ruined and destroyed, but Hemingway was one of the very few people strong enough to resist the hostility of the FBI.”

The FBI “could not differentiate between anti-Fascist and pro-Communist,” and kept tabs on Hemingway for the rest of his life.

Hemingway with Friendless at La Finca Vigia. Date unknown. (Photo Credit: Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.)

In late 1942 Hemingway set up Operation Friendless (named after one of his cats), which entailed patrolling the waters near Cuba in his boat Pilar with a well-trained crew of eight trusted men to watch for German U-boats (submarines).

Nazi U-boats caused immense damage early in the war. 1942 was an especially bad year; the Germans set up “Operation Drumbeat” to destroy supply lines of fuel to Russian and England.

In February of 1942, U-boats destroyed an oil refinery on Aruba that was vital to the British war effort. “In May 1942, German U-boats began to sink merchants in [the Caribbean] at an alarming rate.” By mid-June, U-boats had sunk 360 ships off the eastern coast of the U.S., the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. Army Chief of Staff George Marshall wrote in June 1942 that “losses by submarines off our Atlantic seaboard and in the Caribbean now threaten our entire war effort.”

Hemingway aboard the Pilar; date unknown. (Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.)

When defenses on the Atlantic coastline were strengthened that summer, the U-boats focused their attacks to the south. In June and July, over 30 ships were torpedoed off the Cuban Coast, and by the end of November, 263 ships had been sunk off Cuba. German submariners called this their “Second Happy Time,” the first being 1940 on the Atlantic.

In one especially horrific attack, at 1:00AM on June 29, 1942, 41 miles south of Florida’s Cape San Blas, the British tanker HMS Empire Mica, carrying 47 men and tons of fuel oil for the RAF, was struck by two torpedoes fired from the U-67. The tanker immediately caught fire, staying above water barely long enough for evacuation. Only 14 men were saved, their lifeboat rescued at dawn by two civilian boats.

Although the NY Times and other newspapers reported U-boat attacks, the extent of the attacks and the threat they posed weren’t known by the general public, at the request of the federal government, to avoid panic.

Immediately after Pearl Harbor the U.S. Coast Guard had begun organizing yachtsmen and small boat owners into auxiliary units. And in late June of 1942 the U.S. Navy called for volunteers with boats, promising to equip them with “radio, armament, and…anti-submarine devices.” The volunteer patrols came to be known as the “Hooligan Navy.” Their main responsibility was to watch for submarines. U-boats had to surface, though no one knew how often, to recharge batteries; the more eyes watching, the better the chance of spotting one. The U-boat handbook acknowledged that, noting, “He who sees first, wins.”

Hemingway joined this effort. As a Cuban resident, he had to work through the American Embassy, which supplied Hemingway’s Pilar with radios, bazookas, grenades, bombs, a collapsible rubber boat, a couple of .50-caliber machine guns, and the services of a marine master sergeant.

Hemingway’s plan was to disable a U-boat at sea. He hoped that the Pilar would attract interest from the Germans, who had been stopping small boats in order to seize fresh water, produce, and fish. When the submarine surfaced, the Pilar crew would attack with grenades and light machine guns, then throw an explosive device into the open hatch of the submarine, preventing it from submerging. They would then alert the Navy, which would finish the job.

On July 15, 1942 the tanker Pennsylvania Sun, carrying 107,500 barrels fuel oil from Texas to Belfast, was torpedoed by U-571 in the Gulf of Mexico northwest of Havana, about 125 miles from Key West. Two men were killed; 57 survivors spent over three hours in lifeboats before being picked up by a US Navy ship and taken to Key West. (Photo is in the public domain; US Navy ID Code 80-G-61599)

On December 9, 1942 the Pilar saw a German Model 740 submarine make contact with a Spanish steamer. They reported this immediately, via shortwave radio, to the U.S. Naval Attaché. The submarine sped away on a north-northwest course.

The FBI investigated and claimed to find “negative results.” The U.S. Navy, however, kept that Spanish steamer under close watch for the next few months. And when the Pilar set out again on January 20, 1943, it was assigned to patrol the same area, and “ordered to pay particular attention to the movements” of the Spanish ship, indicating that “not everyone shared the FBI’s skepticism about Hemingway’s earlier report.”

The Pilar crew learned that, several days after they’d seen it, the submarine “landed three men at the mouth of the Mississippi River,” near New Orleans.

Ambassador Braden later wrote that on one occasion the Pilar was “lying off the coast about 100 miles west of Havana in a place where [Hemingway] was sure submarines would surface, when my Naval attaché, for some trivial reason, called him in. The next morning an aviator spotted a submarine in the exact place where Ernest had been lying in wait.”

The critical nature of Hemingway’s efforts was driven home by two tragic incidents. On March 31, 1943 the Pilar returned to home port for repairs. The very next day, a German U-boat torpedoed and sank a Norwegian freighter in that exact patrol area, and two days later an American tanker.

Sneers by Martha Gellhorn and others that Hemingway used the patrols as a way to obtain gas for the Pilar so he could go fishing are either misguided or scurrilous. Of course the crew had to fish; that was their cover. And the fish they caught helped to supplement their diet. But the conditions were uncomfortable at best. The boat was packed with men and equipment. Hemingway himself stood on the bridge from dawn to dusk on a leg that had been shattered and rebuilt in WWI, while the boat rolled and pitched, under a blazing sun with plenty of insects to add to the misery. Equipment and arms took up all the room in the head (bathroom), rendering it unusable. Hemingway would be held financially responsible for the very expensive gear he’d signed for.

In fact, there was a possibility they’d have to throw that gear overboard; it would be a dead give-away of their true intentions should the Germans board the Pilar. Hemingway came up with the idea of posing as a scientific vessel engaged in research on fishing conditions and he hung a sign identifying the Pilar as working for the American Museum of Natural History. The Naval Attache procured a letter to this effect.

The crew faced immense danger. No boat was considered too insignificant by the Nazis. For instance, near Havana one U-boat destroyed a small boat carrying three men and a load of onions. And there was certainly no guarantee that any survivors would be spared; on two separate occasions early in 1942, the Germans torpedoed freighters, then machine gunned the crews as they lowered the life boats.

Hemingway and his three sons at Club de Cazadores, Cuba, in 1945. L-R, Patrick, Jack, Ernest, and Gregory. Jack (known as Bumby ever since his infancy in Paris), while on an OSS mission behind enemy lines, had been shot, captured and held in a POW camp; he was liberated in 1945. The two younger boys joined the Operation Friendless crew for a time; among their other duties, the boys examined a cave with an opening too narrow to accommodate adult men. (Photo credit: Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.)

After a few quiet months in 1943, U-boat activity increased in the Gulf. The Pilar was assigned by the Navy to look in isolated cays for transmitters alerting U-boats of convoys passing in the channel. Here was where small boats were invaluable, since they could get where large ships could not. The Pilar was on the channel each day by 9:00am and “ran inside the reefs, checking the bays and inlets,” “running at trolling speed and noting down any passing traffic for their evening radio report.” As night began to fall they returned to their rough camp, measured the fuel tanks, cleaned up the boat for the next day, sent a coded radio report and took instructions for the next day’s patrol.

The Pilar’s permit expired in early July and the boat, badly in need of repairs, returned to Havana. The FBI, meanwhile, notwithstanding its wartime duties, was spending an inordinate amount of time and energy figuring out how to discredit Hemingway. Five memos were written between April 27 and June 21, 1943. Two were over ten pages each, and detailed extensive investigations of Hemingway’s life and past. On one memo an addendum by Assistant Director Edward Tamm stated, “I see no reason why we should avoid exposing him [Hemingway] as the phoney [sic] he is.”

During Operation Friendless another incident added to the FBI’s hatred of Hemingway. The first mate, wealthy American socialite Winston Guest, was arrested and beaten by the Cuban police. Upon his release, Guest went straight to La Finca and told Hemingway what had happened. Hemingway was furious, and immediately drove Guest to the home of Embassy official Robert Joyce. Because of the close relationship the FBI had with the Cuban authorities, Hemingway suspected FBI involvement or sanction. At Hemingway’s insistence, Joyce summoned Agent Leddy and told him to instruct the Cubans to leave Guest alone.

By mid-1943 the Allies developed technology that ended the U-boat war. The Germans withdrew from the Gulf; “the convoy system and heavy patrols had accomplished their mission.” The Navy gave the Pilar no further assignments. Operation Friendless was over.

Hemingway was in Europe in WWII as a correspondent for Collier’s Magazine. In 1947 he was awarded the Bronze Star for bravery, going “under fire in combat areas in order to obtain an accurate picture of conditions.” (Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.)

Hemingway became a front-line correspondent for Collier’s National Weekly in April 1944. He was at Omaha Beach on D-Day in June, flew on missions with the RAF, and was with Patton’s army in France and at the liberation of Paris on August 25. He was briefly held on charges of being an armed newspaper correspondent. In Luxembourg to cover the Battle of the Bulge, he came down with pneumonia and was hospitalized.

While in England, Hemingway met Mary Welsh, another war correspondent. After the war he returned to La Finca with her, and they were married in 1946.

THE COLD WAR

In 1947, Hemingway supported an expedition (ultimately unsuccessful) to overthrow Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. One of the young revolutionaries involved was Fidel Castro, then in high school.

But Hemingway had “foolishly given money to the cause in the form of personal checks.” A few months later, a friend flew him out of the country ahead of his being arrested for his role in the plot. The Cuban police came to La Finca to search it and held Mary at gunpoint. When the soldiers left, they took all the Hemingways’ guns with them, but returned them the next day. By the time Ernest returned to Cuba, things had blown over.

It would not be the last police raid on La Finca.

It could be said that 1948 was a turning point in the U.S. The Soviet Union, a staunch ally in the War, was now an enemy. The two countries were engaged in an arms race and wrangling over the fate of Europe.

The Hollywood Ten hearings and blacklists had occurred in 1947. In 1948 HUAC took testimony from Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers, and when no indictments resulted, J. Edgar Hoover pressured HUAC to quickly start hearings.

HUAC kept a file on Hemingway, but did not call him. One biographer speculates that this was because the files showed he wasn’t a Communist, but of course that had never stopped HUAC. More likely they feared his fame and stature − and his courage.

Hemingway openly condemned McCarthyism. In the mid-1950s he famously wrote in Look Magazine that he wondered if there was “anything wrong with Sen. Joseph McCarthy (Republican) of Wisconsin which a .577 solid would not cure.”

In 1948 Hoover engaged in massive data collection for anything and everything that could help candidate Thomas Dewey, including information about President Truman. Allegedly Hoover was motivated by Truman’s creation of the CIA, which eroded Hoover’s authority. The FBI was also busily engaged in disrupting the presidential campaign of Henry Wallace, a viable third-party candidate (and, as it turned out, the last such). One newspaper wrote:

“The autumn of 1948 was a dangerous moment in American democracy. As the civilian leader in the war on communism, Hoover was no longer obeying the president….Hoover sought sweeping national security powers over law enforcement and intelligence, sufficient to make him a secret police tsar…Hoover wanted to detain thousands of politically suspect American citizens in the event of a crisis with the Soviets…[he] drew up plans for the mass detention of political suspects in military stockades; a secret prison system for jailing American citizens…”

1948 may also have been a turning point for Hemingway. He began to distrust phones and mail after an “inside source” told him that “censors in Miami had orders to hold all of his mail for two weeks.”

That spring he met A. E. Hotchner, whose employer, Cosmopolitan magazine, sent him to Cuba to ask Hemingway to write an article. The two became friends and created what they called the Hemhotch Syndicate to bet on steeplechases. Later they incorporated in New Jersey as H&H Corporation; under its auspices Hotchner adapted Hemingway’s works and sold them to television, and received 50% of the income.

Hemingway (L) and A. E. Hotchner (R) with unidentified friend in Europe, probably in the 1950s. (Photo Credit: Ernest Hemingway Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.)

Many of Hemingway’s friends disliked and distrusted Hotchner, believing he was on the make and that he brought out the worst in Hemingway. Valerie Danby-Smith, Hemingway’s secretary, described Hotchner surreptitiously taping Hemingway and his friends on many occasions in 1959-60. That may explain the numerous lengthy conversations Hotchner includes word-for-word in Papa Hemingway, a Personal Memoir. He either tape recorded his friends, or changed Hemingway’s letters into conversations without informing the readers (one of Hotchner’s explanations). Neither possibility speaks well of Hotchner’s integrity. (Hotchner offers several explanations, some contradictory, which are included in the notes.)

1948 was also the year that Alfred Rice, who would cause many problems for Hemingway, became his lawyer. Early in their relationship Rice suggested tax loopholes; Hemingway told him that no “dishonorable, shady, borderline, or ‘fast’” action would be taken and that Hemingway himself, not Rice, would judge whether an action was “honorable and ethnical, not simply legally, but according to my own personal standards.”

The Old Man and The Sea was written in 1951 and published September 1, 1952, both in Life Magazine and as a hardcover book of the month club selection.

In January 1954, Hemingway and Mary were in Africa when their plane crashed. They escaped serious injury but the plane couldn’t be used, and a second plane was sent to rescue them. That plane also crashed, and caught fire. Mary and the pilot were able to squeeze out but Hemingway was too big. He had to use his head as a battering ram. Because the accident occurred far from a major city, he was not hospitalized for several days, and most of his injuries were not diagnosed for weeks. They included a fractured skull; ruptured spleen, kidney and liver; crushed vertebrae; first degree burns; dislocated shoulder; and a paralyzed sphincter. He also temporarily lost his vision in one eye and hearing in one ear. His skull was actually “broken open.”

Afterward Hemingway aged visibly and became, in the words of some of his friends, old. He was 55.

In October 1954, he won the Nobel Prize for literature.

A year later, he nearly died from a kidney infection and other organ diseases caused by the accident. He tired more easily and for a long time he could not travel. The lack of physical vitality was completely new to him. Writing was physically difficult. He could not sit for very long, due to the injury to his spine, and did his writing while standing.

He continued to write and worked on several books, but for the last ten years of his life he published none. Both A Moveable Feast and Islands in the Stream were published posthumously.

By this time Hemingway considered Cuba his home, although he spent time in Idaho every year. Most of his books, research, art and memorabilia were at La Finca Vigia. And so were most of his pets. One was a dog Hemingway and Mary had befriended in Idaho in winter of 1947-48 who had become Hemingway’s constant companion: Black Dog.

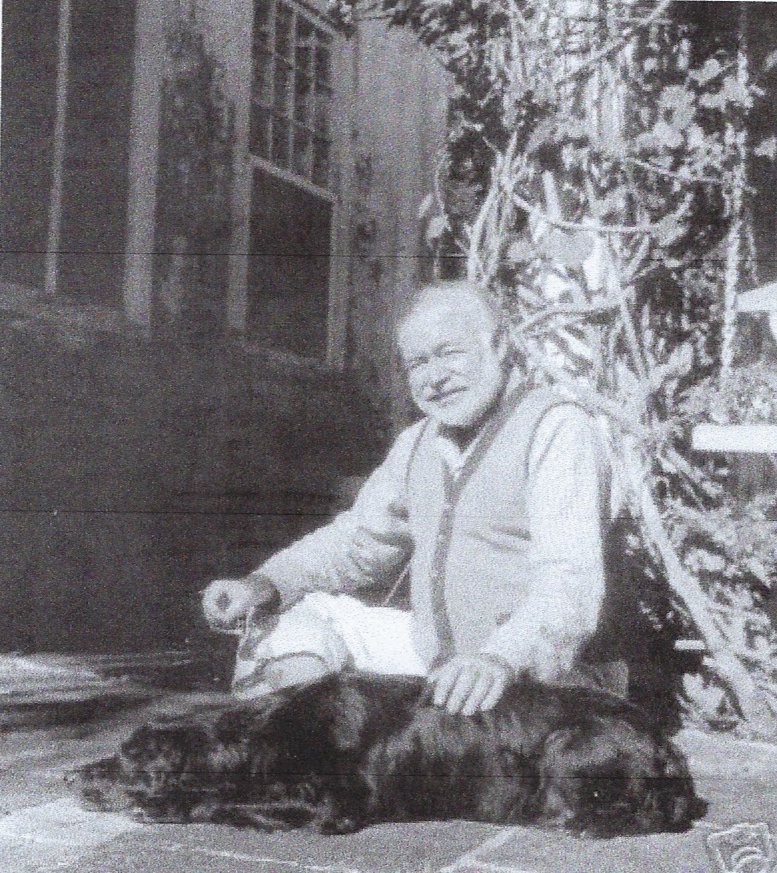

Hemingway and Black Dog at La Finca Vigia.(Ernest Hemingway Collection, JFK Presidential Library & Museum, Boston)

REVOLUTION IN CUBA

In late 1956 Batista’s police searched La Finca, looking for rebel guns. Apparently Hemingway’s status as a Nobel Prize winner was no deterrent to the increasingly desperate Batista regime. Black Dog, old and nearly blind and deaf, snapped at a soldier, who struck the animal in the head with a rifle butt and killed him. Hemingway was devastated and, “ignoring the urgent advice from everyone,” lodged a formal complaint. Nothing came of the complaint, but the Cuban people knew of it and respected Hemingway enormously for making it.

Hemingway “never completely recovered from the loss of Black Dog.” Four years later he still mourned.

In early 1957, Herbert Matthews of the New York Times came to Cuba to meet with the rebels and to disprove Batista’s claim that Castro was dead. He dined at La Finca with his old friend Hemingway (they’d both worked in Spain as journalists and both supported the Republic). Hemingway encouraged Matthews’s praise of and respect for Castro. Matthews later expressed appreciation since he was otherwise standing alone among U.S. newspapermen.

Hemingway got another dog, Machakos, to provide some protection against Batista’s soldiers. But at 4 a.m. one morning in August 1957 La Finca was again raided by a government patrol looking for a rebel fugitive. A soldier shot and killed Machakos.

Months later, Hemingway wrote to a friend that the soldier who had killed Machakos and “tortured several of the boys of the village” had himself been executed by “the boys of Cottorro” (revolutionaries).

Hemingway was concerned about another raid should his political profile increase, and so, a few months after that second raid, he and his Cuban first mate Gregorio Fuentes went out on the Pilar and threw an assortment of guns into the sea. Fuentes later said these were arms that Hemingway had allowed him to hide for the revolutionary movement.

After Castro called for a general strike and Batista authorized citizens to shoot strikers, most Cubans avoided public places. When the guerrillas began kidnapping Americans in Cuba, Hemingway wrote a friend that

“Kidnappings are the latest local sport. They now have mining engineers, sugar mill technicians, consular officials, seamen (all ratings) and Marines − I called the Embassy to ask when they were going to start picking up the F.B.I.”

Meanwhile Hemingway had to deal with an attempt by his lawyer, Alfred Rice, to disgrace Hemingway’s political integrity. Hemingway had refused Esquire magazine permission to republish some of his stories in an anthology because he was planning to revise and publish them himself in a new collection; as a peace offering, he said that Esquire could publish one story. But Rice filed court papers arguing that Hemingway would be damaged if the stories were reprinted because they’d been written when the Soviet Union was an ally but it was now “our greatest enemy.” This was reported by The New York Times. Hemingway immediately contacted the Times, which ran a story the next day reporting that Hemingway “sharply denied” that his views had changed. “Those statements were made by my lawyer, Alfred Rice, and I have just called him up and given him hell for it.”

Hemingway divided his time between Cuba and Ketchum, Idaho, and was in Ketchum in January 1959 when the Cuban Revolution was successful.

A Cuban friend called Hemingway right away to say he’d been appointed as head of the provisional government and was personally protecting La Finca. Hemingway also heard from New York Times reporter Matthews and from people working at La Finca that all was well there.

News services immediately called Hemingway for comment. “I believe in the historical necessity for the Cuban revolution, and I believe in its long range aims,” Hemingway told newspapers. Enlarging his statement for the New York Times, he added that he was “delighted” with the Revolution. Upon Mary’s urging, he changed “delighted” to “hopeful.”

When the Cuban government immediately began putting Batista’s soldiers on trial, newspapers and politicians in the United States expressed concern and outrage. “Executions in Cuba Protested,” “Military Court in Cuba Dooms 14 for ‘War Crimes’; Senator Morse Urges End of ‘Blood Baths’”, “US Will Speed Envoy to Havana”, “The Spectacle in Havana” are just some of the headlines in the New York Times in January 1959.

A newspaper article headlined “Hemingway Defends Cuban Trials” was published on January 23, 1959. A second article, headlined “Hemingway Talks on Cuba; ‘I’ve Great Hope for Castro,’ Says Trials, Executions of Batistans Necessary” was published on March 9, 1959. Neither article ran in a major newspaper.

The first, published alongside a description of the first trial of a Batista soldier, ran in the Eugene (Oregon) Register-Guard and cited a telephone interview on radio station KING, in which “Hemingway condemned the Batista group as torturers and murderers.” Hemingway added that twelve boys from his own village in Cuba had been tortured and killed, and concluded, “I don’t think people outside the country have any business to criticize the justice of the trials since the trials are public and witnesses are heard and an impartial decision is given.”

The second article was published in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. The writer had spent an afternoon with Hemingway in Ketchum. “I believe in the cause of the Cuban people,” Hemingway said. While some of Batista’s officials and police were good and honest, many were “thieves, sadists and torturers. They tortured kids.” Hemingway said that bodies were found horribly mutilated and he “cataloged in unprintable details the methods of torture used by Batista police.” He said that if the government didn’t execute the torturers, the people would, and vendettas would follow. The trials gave people a respect for law and order. And the revolution depended in part on a promise to the Cuban people that those responsible for atrocities would be punished. Regarding one man who’d been executed recently, “ ‘I know him,’ he said. ‘If they shot him a hundred times it wouldn’t be enough punishment for the terrible things he has done.’”

Front page of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer of March 9, 1959.

Hemingway returned to Cuba on March 29, 1959 and stayed until April 22. Meanwhile, in February the United States had assigned a new ambassador to Cuba: Philip Bonsal.

Upon learning of the Cubans’ proposed trip to the United Nations, Hemingway asked for a meeting with Castro, to brief the Cubans on American politicians and to warn them of tricks and traps by the media and of heckling. Castro sent an associate who met with Hemingway for several hours. When he left, Hemingway asked him to let his comrades know that he strongly supported the actions of the revolution.

In July Castro appeared on the American TV show “This Is Your Life”, and quoted Hemingway as approving executions of military criminals in Cuba.

From May until October, 1959, Hemingway was in Spain. On November 4, 1959, he flew into Cuba and held a press conference at Rancho Boyeros (now José Martí) Airport. American Embassy employee J. L. Topping immediately reported to the FBI that Hemingway told journalists he completely supported the Castro government and that it was best thing that had ever happened to Cuba; that he didn’t believe information published abroad against Cuba; and that he sympathized with the Cuban government and “all our difficulties.” Topping added that Hemingway himself had emphasized “our” and when asked about that, said he hoped Cubans wouldn’t regard him as Yanqui but as another Cuban. With that, he kissed the Cuban flag.

The Hemingways went back and forth from Ketchum to Cuba over the next few months. In early March, Anastas Mikoyan, the Soviet foreign minister in Havana, visited La Finca. Mikoyan was a great admirer of Hemingway and presented him with Russian translations of his complete works. Mikoyan promised Hemingway the royalties he was due, which had been frozen in the USSR, but Hemingway said he could not accept unless royalties were paid to all American writers published in the USSR.

When the Hemingways returned to Ketchum for hunting season, they were driving through town on a snowy night when Hemingway noticed lights on at the bank. One friend with him guessed it was the cleaning ladies; the other friend thought it must be the bank manager working late. Hemingway disagreed and said that the FBI was checking his accounts because “they want to get something on us.” Mary told him he must be tired. She later wrote that she’d never seen him “so disturbed about an imagined, illusory threat.”

According to one source, Hemingway “said several times that he wanted to write a book about the Cuban Revolution.”

In May 1960, Hemingway and Fidel Castro met for the only time. Both attended the annual Hemingway fishing competition. Castro told Hemingway that the strategy used by the guerrillas in For Whom the Bell Tolls had given him ideas that were put to use by Cuban revolutionaries in the Sierra Maestra. Many photographs were taken; Hemingway had several prints developed and sent one to the Cuban premier with a dedication, “To Dr. Fidel Castro…in friendship.” Castro kept the photograph on his office wall next to a picture of his father.

Hemingway and Fidel Castro in May, 1960 in Havana.

That same month, May 1960, Raymond G. Leddy, who was now working for the State Department, testified to a Senate subcommittee on the dangers posed by Fidel Castro.

A few months earlier, in March 1960, a French freighter, La Coubre, unloading 76 tons of munitions in Havana, suddenly exploded. 100 people died. Cuba accused the U.S. of sabotage. On June 30, Cuba nationalized the Texaco refinery. The appropriation was greeted with outrage in the United States, but the press neglected to mention that Texaco and other oil companies were refusing to refine crude oil for Cuba.

Hemingway presciently remarked to Hotchner, “I hope to Christ the United States doesn’t cut the sugar quota. That would really tear it. It will make Cuba a gift to the Russians.” But in July the U.S. reduced its quota of Cuban sugar. The USSR picked up the slack.

Despite his awareness of the tension between the two countries that he believed was becoming dangerous and irrevocable, Hemingway continued to travel back and forth for a period of nineteen months after the Revolution. Diplomacy still existed, albeit an uneasy one. Travel wasn’t prohibited and many Americans visited Cuba. La Finca was often host to visitors, including Antonio Ordóñez, the Spanish bullfighter; Hotchner; the journalist Herbert Matthews; and friends from Idaho and Key West. Valerie Danby-Smith later wrote that “a number of other friends from the States popped over to Havana that spring [1960].” Hemingway also ran into famous people in Havana in 1959 and 1960, including Joseph Alsop, critic Kenneth Tynan, journalist George Plimpton, and playwright Tennessee Williams. Given that, and because of his fame and prestige, perhaps Hemingway believed his continued residency in Cuba was not endangered.

THE ULTIMATUM

In early 1960, a seminal event occurred, one that went unreported in the press and has even been omitted by most Hemingway biographers. Ambassador Bonsal came to La Finca and told Hemingway that the U.S. was probably going to break diplomatic relations with Cuba, and that “Washington” wanted Hemingway to stop living in Cuba and to denounce Castro and the Cuban regime. Hemingway objected to doing either. Bonsal pressed harder: He said that Hemingway’s high-profile presence in Havana could become an embarrassment to the United States. He added that discussions amongst officials had included the word “traitor.”

Hemingway was shaken by the threat but didn’t back down. He stayed “at his home [in Cuba] working as a deliberate gesture to show his sympathy and support for the Castro Revolution.”

The night before Ambassador Bonsal left for the U.S. in late January, he visited La Finca again and reiterated the ultimatum. It had become even more important, he said, for Hemingway to “make an open choice between his country and his home — loudly and clearly, so the world would know where he stood.”

Hemingway still did not denounce the Cuban Revolution or Fidel Castro.

On July 25, Hemingway left for Key West. He planned on returning in the autumn and left La Finca fully staffed. He didn’t bring his books, paintings, or many of his manuscripts. He deliberately left without fanfare so that no one would think his leaving could be misinterpreted as a statement against Castro, whom he continued to support.

He would never be able to return.

The United States had already begun covert plans to overthrow the Cuban government, and on August 18, 1960, President Eisenhower authorized $13 Million in funding to a group created by the Deputy Director of the CIA. A few months later the CIA began training thousands of ex-Cubans in a plan to invade Cuba. The plan was called “Operation Zapata” and when it was put into action in April of 1961 it became known to history as the Bay of Pigs.

On Sept 20, 1960, Castro led a large Cuban delegation to New York City for meetings at the United Nations. This was the famous visit during which the Cubans stayed at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem and dined with the hotel workers while thousands of supporters filled the streets of Harlem.

Thousands lined the streets in Harlem in support of Fidel Castro and the Cuban revolution. Outraged over a midtown hotel’s demand for a $10,000 deposit, Castro said the Cubans would rather sleep in Central Park. They were invited to the Hotel Theresa by its proprietor, Love Woods, who gave the Cuban delegation forty rooms. Castro said he felt much more at home in Harlem among the black proletariat of America. The enthusiastic welcome given, impromptu, by thousands of New Yorkers to the Cuban revolutionaries must have dismayed U.S. officials planning attacks on Cuba and who had, just a few months earlier, demanded that Hemingway denounce the Cuban Revolution, which he refused to do.

Castro’s speech to the UN was on September 26. The delegation returned to Cuba on September 28. On September 30 the U.S. told diplomats and others to send their wives and children home. On October 15, Cuba began the most extensive nationalization ever in the western hemisphere. The U.S. trade embargo was announced on October 19, and Ambassador Bonsal was recalled on October 20. Cuba’s nationalization continued on October 25.

Most properties owned by US citizens were nationalized. La Finca Vigia was not.

After spending a few months in Spain for research, Hemingway joined Mary in New York City on October 10, 1960, and holed up in her apartment because he believed he was being followed. Mary “lost patience and asked him to quit acting like a fugitive from justice.”

They soon left for Ketchum. Arriving at the Idaho train station, Hemingway glanced across the street, noticed two men in topcoats, and said they were agents tailing him. Mary observed that the men were not wearing “the usual Western dress of parkas or ranchers’ garb,” but told Hemingway not to be silly.

BETRAYAL AND INCARCERATION

In November 1960, a month after he got to Ketchum, Hemingway and a friend picked up Hotchner at the same train station and Hemingway said that agents had followed them from Ketchum, that his car and phone were bugged, and that his mail had been intercepted. Hemingway also referred to a phone call he’d had with Hotchner that was cut off in such a way that he suspected a wiretap gone awry but Hotchner argued against there being any sinister reason for the malfunction. When they arrived in Ketchum that night, Hemingway pointed out the bank lights with two men working in back at a counter. They were auditors, he said, going through his accounts.

Nowadays these incidents are cited as proof of Hemingway’s paranoia. But in rural Idaho in 1960, men did not wear suits; people did not work in offices late at night as they do today; and the town was more or less shut down, with only one bar open, because no snow had fallen yet so the ski lifts at Sun Valley hadn’t been started up and no skiers were in town.

The idea that the U.S. Government might harass a world-famous Nobel Prize winning writer, might even monitor his bank accounts, was made to seem ludicrous, even crazy. Mary and Hotchner and other friends didn’t seem to notice, or would not admit, that the growing tension between the United States and Cuba made Hemingway’s fears realistic.

Among Hemingway’s supposedly delusional worries was whether enough money had been set aside for his taxes, a fear that Mary thought unreasonable. But it wasn’t. His lawyer-accountant, Alfred Rice, had just the previous year “grossly miscalculated” Hemingway’s estimated taxes, resulting in “Ernest receiving a hefty fine and having to borrow to meet the extra money owed.”

Hemingway wanted all his financial dealings to be completely legal, above-board, with all taxes paid; otherwise he could be prosecuted over a technicality. Mary and others repeatedly ridiculed such concerns, both to Hemingway and after his death. In 1960, for instance, Mary inexplicably refused to set his mind at ease by showing him check stubs proving that they had paid the Social Security tax for their housecleaner.

Hemingway also continued to worry about repercussions from an immigration problem with his friend and secretary, Valerie Danby-Smith, an Irish national. When the Hemingways and Valerie went from Cuba to Key West in July 1960, at a time of high tension between the two countries (and after the threat relayed by Ambassador Bonsal), an immigration officer noticed that Valerie’s visitor’s visa hadn’t been renewed. He let her into the U.S. but told her to renew the visa. This, writes Mary, sent Ernest into a “disproportionately large tizzy.” But such minor violations of law do provide excuses for prosecution of political enemies.

Mary tried to convince him to see a psychiatrist, but he wouldn’t; he was “fixated” about the FBI. This so-called fixation was the primary “evidence” that he was losing his mind.

In November of 1960, Mary and Hotchner concocted a plan to trick Hemingway into a mental hospital. Hotchner offered to “take over” the situation and go to New York to consult a “very fine psychiatrist” he knew. But before that, he met with George Saviers, Hemingway’s friend and physician in Ketchum, to figure out how they could get Hemingway’s cooperation. Hotchner suggested Dr. Saviers pretend to find Hemingway’s blood pressure significantly raised, enough that he would have to go to a facility recommended by the New York doctor.

Hotchner then visited the New York psychiatrist, Dr. James Cottell, who “acted quickly.” Based solely on Hotchner’s descriptions, Dr. Cottell came up with a diagnosis of Hemingway − whom he’d never met − and suggested the Mayo Clinic since it had both physical and psychiatric facilities “so that Ernest could be admitted for some physical ailment, thereby masking his true malady.” Dr. Cottell made all the arrangements and had conversations with the Mayo doctors ahead of time.

Meanwhile, in Ketchum, Hotchner noted that “Ernest…reacted to the increased-blood-pressure readings with the alarm we had anticipated, and [Saviers] said he thought he might be able to get Ernest to go to Mayo on the basis of blood pressure tests and special treatment.”

Hemingway did, in fact, think he was going to the Mayo for treatment of his many physical problems.

Instead, he was committed.

Dr. Howard Rome was the doctor in charge of Hemingway’s psychiatric evaluation. He found “no appreciable decline in…his delusions of persecution and poverty,” and ordered a series of electric shock treatments. Hemingway was shocked between eleven and fifteen times in December 1960 and early January 1961.

The ECT was administered despite the fact that Hemingway had had at least eight concussions in his life and had suffered serious brain trauma in the Kenyan plane crash. Also, high voltage was used, adding to the possibility of brain damage even without Hemingway’s concussion history.

Hemingway was not allowed to make or receive phone calls. He was frisked routinely. His room had double-locked doors and heavily barred windows. A light burned all night long.

When Hotchner visited, Hemingway told him that he believed his room at the hospital was bugged. “He suspected that one of the interns was a Fed in disguise.” Hotchner says he thought this was another delusion.

FBI documents released decades later established that Dr. Rome was reporting on Hemingway’s condition to the FBI’s Minnesota office.

The Mayo doctors also discontinued the anti-hypertension drug that had been keeping Hemingway’s blood pressure under control, because they thought the drug was causing depression, as evidenced by Hemingway “suffering delusions and feelings of persecution.”

Hemingway was discharged from the Mayo Clinic January 22, 1961. He returned to Idaho in a greatly deteriorated physical condition. He had lost nearly 40 pounds during those two months at the clinic and was emaciated.

But worst of all: he could no longer write. The electric shock “therapy” had destroyed his memory and with it his creative ability.

As he told Hotchner, in a famous quote, “It was a brilliant cure but we lost the patient.”

Hemingway was not the only prominent American during that period to be given electric shock. It was also done to Sylvia Plath, William Faulkner, Vivien Leigh, Judy Garland, and Frances Farmer, an actress and social activist who may also have been lobotomized. In September 1961, two months after Hemingway’s death, Paul Robeson was institutionalized in a London clinic where he received 54 electric shock treatments. He never recovered.

Hemingway continued to assert that he was being spied on and conspired against. His mistrust of the people around him had increased. These attitudes were, his “friends” claimed, indications of his continuing mental degeneration.

Oddly, they don’t seem to regard their having tricked him into being committed to a mental institution as a reason for mistrust.

His concerns were real, but Mary disparaged all of them. Hotchner thought his worries proved he was losing his mind. Saviers was convinced of that. All three lied to Hemingway often. Hotchner even kept Hemingway’s friend Gary Cooper away and didn’t tell Cooper what was being done to Hemingway at the Mayo. Valerie was in New York, absorbed in a new job. There was no one Hemingway could trust who was also politically savvy. Hemingway was isolated, and that made him vulnerable.

In February he was asked to write a short tribute to President Kennedy. He stood at his desk every day for hours. The words would not come. It took him a week to write a few simple sentences.

He was devastated − yet not completely broken. He continued to send money to the Cuban staff at La Finca, and routed it through Canadian banks. He worked on the Paris memoir, and wrote that, “this book contains material from the remises of my memory and of my heart. Even if the one has been tampered with and the other does not exist.”

And he still didn’t denounce Cuba.

On April 15, 1961, Cuban ground forces in Cienfuegos shoot at a bomber. The attackers were funded by the CIA and their weapons included American B-26 bombers painted to look like stolen Cuban planes. (Photo: warhistoryonline.com)

On April 15, 1961, the Bay of Pigs invasion occurred. It was a military and political disaster for the United States.

The FBI then informed Hemingway that he would not be allowed to return to Cuba. “This was devastating as it meant that he could not go back to his farm, his boat, his library of 9,000 books, his paintings, his unfinished manuscripts, and his family of dogs and fifty-seven cats…”

On April 21 Mary woke to find him in the kitchen with a gun. She talked to him for almost an hour until Dr. Saviers arrived and disarmed Hemingway, then took him to a local hospital where he was sedated.

Saviers and two other friends flew Hemingway, against his will, back to the Mayo Clinic. On the way, he made two more suicide attempts.

Before entering the Mayo, Hemingway had not been seen by a psychiatrist. Nor had he ever attempted suicide until after receiving electric shock.

Over the next two months he was given another ten electric shock treatments.

During that period he was not allowed to make or receive phone calls or to have visitors, “not even his wife Mary.” When he did speak with Mary, Hemingway accused her of responsibility for, or collusion in, the shock treatments. She took this (or claimed she took it) as further indication of Hemingway’s mental illness.

But she realized that the ECT wasn’t helping, and wanted to get him into the Institute of Living in Hartford, CT, a facility set up for long term recovery in a less prison-like sanitarium. She asked Dr. Rome to recommend this, but he did not. Instead, he set up a “conjugal visit” that went horribly. Mary assumed the visit would be in her hotel room, but Dr. Rome refused; they had to meet “in the locked, barred wing of the hospital…other inmates pushed through the door…Ernest seemed to accept them as part of his incarceration, but they unnerved me. Our ‘solitude’ was not entirely satisfactory to either of us…”

Dr. Rome wrote that Hemingway “frequently” discussed suicide with him, promising not that he wouldn’t commit suicide, only that he would not do it at the Mayo.

Hemingway was released in June and returned to Idaho. He no longer harbored any hope of ever being able to write again.

The second night back, while at a local restaurant with Mary and a friend, Hemingway saw two men in “city clothes” and remarked that they might be FBI agents.

The next morning he was dead from a double-barrel shotgun blast.

* * * *

Almost inconceivably, considering Hemingway’s stature, no inquest was held. The gun he’d been shot with was destroyed within two weeks.

New York Times, July 4, 1961, page 9

A New York Times article published three days after Hemingway’s death reports “the coroner said that an inquest was not mandatory because there had been no evidence of foul play.” The Coroner’s decision was made after a meeting with the Sheriff, prosecuting attorney, Mary, and Hemingway’s oldest son. No sources describe any official making more than a cursory examination. The first doctor to arrive concluded after “a brief examination that Ernest had died of a self-inflicted” gunshot to the head. The death was ruled to have been caused by either accident or suicide.

I have found no evidence that the gun was tested for fingerprints, or that Hemingway’s hands (or the hands of Mary or those of George Brown, who was staying in the guest house) were tested for gunshot residue. I also found no evidence that an autopsy was conducted. Baker’s endnote adds that the sheriff impounded the shotgun for about two weeks, and when it was returned, Mary had friends destroy it to avoid its becoming a souvenir. A recent book confirms the destruction of the gun. A welder used a torch on the steel parts, the stock was smashed, and the mangled remains were buried in a field.

Despite Hemingway’s previous suicide attempts, Mary had locked up the guns but left the keys where they had always been kept. “I thought of hiding the keys, and decided that no one had a right to deny a man access to his possessions, and also assumed that Ernest would not remember the storeroom.” Mary doesn’t seem aware of the contradictions in her explanation.

Pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request by scholar/writer Jeffrey Meyers, the FBI released a 124 page file on Hemingway in 1983. Almost all of the documents (some heavily redacted) pertained to the work he’d done in Cuba during WWII. Only one document refers to the Mayo Clinic, and it establishes that Dr. Rome (whose name is blacked out) contacted the FBI at least once.

Cuban postage stamp of Hemingway (Courtesy of Hunter Havens)

According to that memo, Hemingway was worried that his having registered under the name of his friend Dr. George Saviers would cause problems for Saviers with the FBI, and the FBI told the Mayo to reassure Hemingway that this wasn’t a problem. In one fell swoop, the FBI comes up with a benign explanation for its contact with the Mayo, and limits the contact to one occasion. Pardon my skepticism.

There is also a letter to J. Edgar Hoover a few years after Hemingway’s death written by a friend at Mary Hemingway’s behest, explaining that she’d had nothing to do with the commemorative stamp issued by Cuba. The stamp was included, along with Mary’s request that it be returned to her. At the bottom of the letter, in Hoover’s handwriting, is a note:

“Return it. See that appropriate notation is made in our files. Knowing Hemingway as I did I doubt he had any communist leanings. He was a rough, tough guy & always for the underdog.”

A cynical reader may notice the complete change of Hoover’s tone now that Hemingway was dead.

The only document pertaining to the Cuban Revolution is the J. L. Topping report of November 6, 1959 referred to earlier. The subject of Topping’s memo is “Ernest Hemingway Gives Views on Cuban Situation.” It describes Hemingway’s statements at the Havana airport with special concern over his kissing the Cuban flag and using the word “our” regarding Cuba’s difficulties. The document ends mid-sentence shortly after the “Begin Official Use Only” section begins. There is no indication of how many pages follow.

No more documents have been released. At least 15 pages (according to the FBI) remain classified.

Mary inherited everything, including the copyrights. She became a wealthy woman, managing Hemingway’s estate “with shrewdness and tenacity.” After Hemingway’s funeral the Cubans contacted her and asked for her consent to turn La Finca into a monument to Hemingway. She agreed, contingent on her being allowed to retrieve papers and personal belongings. The Cubans agreed.

Even in the country’s most dire economic times, there has always been a full-time caretaker assigned to La Finca.

A Moveable Feast was published posthumously, edited by Mary and titled by Hotchner. Three days before his death, Hemingway drafted (but did not mail) a letter to his publisher saying that the memoir could not be published in its current condition because it was unfair to Hadley (his first wife), Pauline (his second wife) and F. Scott Fitzgerald. But Mary ignored those concerns.

Although A Moveable Feast gives a wonderfully descriptive portrait of his and Hadley’s life in Paris in the 1920s, and although it contains much generosity toward others (such as Sylvia Beach), there are some startlingly private anecdotes and cruel portrayals in the book that have been used ever since to show Hemingway’s supposed viciousness toward his friends F. Scott Fitzgerald and Gertrude Stein, among others.

However, the book is beautifully written and Jeffrey Meyers believes this indicated that Hemingway had “regained the full force of his literary power only months before he entered the Mayo Clinic.” Except for The Old Man and the Sea, Hemingway’s work since 1940 had not equaled his earlier brilliance. If he was writing in 1960 as powerfully as he had in For Whom the Bell Tolls, and with the rage and sense of justice that had motivated him to write “Who Murdered the Vets?”, then those U. S. officials intending to overthrow the Cuban government had a big problem.

Hotchner, who said his partnership with Hemingway had been “lucrative,” published his memoir Papa Hemingway in 1966. He was also a neighbor and friend of Paul Newman, with whom he formed Newman’s Own, the non-profit food company, in 1982.

Hemingway’s suspicions of his lawyer-accountant, Alfred Rice, were not evidence of paranoia; Rice was stealing from Hemingway. After Mary’s death in 1986, Hemingway’s sons learned that Rice had secret Swiss bank accounts and had been taking a 30% commission instead of the usual 10%. “The sons sued Rice, who escaped being jailed for fraud and embezzlement by dying in April 1989.”

Martha Gellhorn had what amounted to a second career as the supposed victim of Hemingway’s fame, complaining often that her writings had been unfairly overshadowed by his and that people only knew her as Hemingway’s wife even decades later. But one Hemingway expert believes that the very reason Martha married Hemingway was to advance her journalism career. Jeffrey Meyers writes that in the 40 years after Hemingway’s death, “while ostensibly refusing to discuss Hemingway, she [Gellhorn] constructed a careful, sanitized view of her own behavior, which stressed her independent achievement as a writer and journalist.”

Many writers have continued to sanitize Gellhorn. For instance, a recent biography omits the fact that she had to leave Africa after living there over a decade when she ran over and killed a child in Kenya.

In 1964 Martha began the “best and longest relationship of her life.” It was with Laurance Rockefeller.

In 1964, Dr. Howard Rome provided the Warren Commission with a “psychological autopsy” of Lee Harvey Oswald.

In 2011, Hotchner wrote an editorial in the New York Times, admitting he’d been wrong not to believe Hemingway’s fears of being monitored by the FBI.

In 2015 Hotchner wrote another memoir about Hemingway. The book opens and closes with Hotchner’s visit to Hemingway at the Mayo in June 1961. During the visit Hotchner advised Hemingway to “get over this craziness” of believing he was being monitored by the FBI. “Why would the FBI….,” he asked, not finishing the sentence. Hemingway replied:

“I write suspicious books that take place in foreign countries: France and Italy, Communist Cuba and fascist Spain. I lived among the Cuban Communists all those years. I shoot guns. I speak languages J. Edgar Hoover doesn’t understand. My lawyer, my doctor, my banker, all of them in cahoots with him.”

Coda

Hemingway, the greatest American writer of the 20th century, was popular world wide. He was a stalwart anti-fascist all his life. He refused to become an anti-communist despite continued pressure to do so. His strength of character, uncompromising integrity, and great courage made him a huge obstacle to the efforts of the U.S. government to turn the American people against Cuba.

The U.S. had already used means both aboveboard (such as the embargoes) and clandestine (attempted assassinations of Castro, the Bay of Pigs invasion, training of mercenaries by the CIA, and manipulation of the media, to name a few) to try to oust the Cuban government. It intended on employing such means in the future. It could not afford to have one of America’s best known writers living in Cuba and thus be able to expose lies and, worse, to object to attacks. It certainly could not afford to have Hemingway write a book supportive of the Cuban Revolution.

From that perspective, Hemingway was extremely dangerous.

Hemingway duck-hunting in Idaho, October 1941. (Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston)

Headline photo: Hemingway aboard the Pilar aiming a tommygun, 1935. Courtesy of wikimedia (public domain).